03HaKOMwrreAb1--ra¶ Konuq - fren lish.ru Short stories by well-kno

American and British detective and adventure story writers will carry the reader into the world ofadventure and intrigue. Disappearance ofpeople, magic and a robbery arejust some ofthe highlights ofthe plot which make the book immediately appealing to reluctant readers.

ginner

Element

HWIMHa'O[U

termediate aq npoawwmouux porpypoBHR

Advanced

AJ1q coBepmeHcTBY10ruuxcq

'9 78581 1 2 31 9

g Kny6

6a1UIJIJ1a

llP11KJlnqeHqeCKHe

ii Wit!

The Stolen ac s and other adventure stories

ознакомительная копия english.ru

Advanced

Английский клуб Украденная

Английский клуб Украденная ![]() бацилла

бацилла ![]()

и другие приключенческие рассказы

![]() Книга для чтения на английском языке

в старших классах среДних школ,

Книга для чтения на английском языке

в старших классах среДних школ, ![]() лицеях, гимназиях, на I—II курсах неязыковых вузов

лицеях, гимназиях, на I—II курсах неязыковых вузов

МОСКВА

ТРИС ПРЕСС

2008

ознакомительная копия - еп ish.ru удк

811.111(075) ББК 81.2Англ-9З

ознакомительная копия - еп ish.ru удк

811.111(075) ББК 81.2Англ-9З

У45

Адаптация текста, словарь: Г. К. МагиДсон-Степанова

Упражнения: Г. И. БарДина

Серия «Английский

клуб» включает книги и учебные пособия, рассчитанные на пять этапов изучения

английского языка: Elementary (для начинающих), Ртеlntermediate (для

продолжающих первого уровня), Intermediate (для продолжающих второго уровня),

Upper Intermediate (для продолжающих третьего уров![]() ня) и Advanced (для

совершенствующихся).

ня) и Advanced (для

совершенствующихся).

Серийное оформление А. М. шагового

Украденная

бацилла и другие приключенческие рассказы У45 [The Stolen Bacillus and other

adventure stories / адаптация текста, словарь Г. К. Магидсон-Степановой;

упражнения Г. И. Бардиной]. — М.: Айрис-пресс, 2008. — 160 с.: ил. ![]() (Английский

клуб). — (Домашнее чтение).

(Английский

клуб). — (Домашнее чтение).

ISBN 978-5-8112-3190-4

Сборник приключенческих и детективных рассказов содержит произведения английских и американских писателей XIX—XX веков в адаптащи Г. К. Магидсон-Степановой. Книга рассчктана на учащихся старших классов средних школ, лицеев, гимназий, студентов [—ll курсов неязыковых вузов. После каждого рассказа приводятся упражнения, направленные на овладение лексикой, грамматикой и развитие навыков общения. Книга содержит словарь.

ББК 81.2Антл-9З удк 811.111(075)

С] ООО «Издательство «АИ РИСпресс», оформление, адаптация текста, упражнения и словарь, fSBN 978-5-8112-3190-4 2002

ТНЕ ADVENTURE

[п 1895 Мг Sherlock Holmes and spent some weeks in опе ofour great University towns. lt was during this timel that the facts which ат going to tell,you about took place.2

Опе evening we received а visit йот а certain Мг Hilton Soames, а lecturer at the College of St. Luke's.3 Мг Soames was so excited that it was clear that something very unusual had happened.

![]() hope, Мг.

Holmes,” he said, ”that уои сап give те а few hours of your time. А very

unpleasant thing has taken place at our college and don't know what to do.”

hope, Мг.

Holmes,” he said, ”that уои сап give те а few hours of your time. А very

unpleasant thing has taken place at our college and don't know what to do.”

it was during this time — как раз в это время (эмфатическая конструкция)

2 to take place — произойти з College of St. Luke's ['seint 'lu:ks] — Колледж святого Луки

з

03HaK0MwreAbHa¶

![]() "I am very' busy

just now," my friend answered. "Could you call the police?"

"I am very' busy

just now," my friend answered. "Could you call the police?"

"No, no, my dear sir, that

is absolutely impossible. It isjust one ![]() of these cases when it

is quite necessary to avoid scandal. I am sure you will keep our secret. You

are the only man in the world who can help me. I beg you, Mr. Holmes, to do

what you can. '

of these cases when it

is quite necessary to avoid scandal. I am sure you will keep our secret. You

are the only man in the world who can help me. I beg you, Mr. Holmes, to do

what you can. '![]()

Holmes agreed, though very unwillingly, and our visitor began his stow.

![]() 'I must explain to you,

Mr. Holmes," he said, "that tomorrow is the first day ofthe

examination for the Fortescue Scholarship. I I am one ofthe examiners. My

subject is Greek. The first ofthe examination papers consists of a piece of

Greek translation which the candidates for the scholarship have not seen

before. Of course, every candidate would be happy if he could see it before the

examination and prepare it in advance? So much care is taken to keep it secret.

'I must explain to you,

Mr. Holmes," he said, "that tomorrow is the first day ofthe

examination for the Fortescue Scholarship. I I am one ofthe examiners. My

subject is Greek. The first ofthe examination papers consists of a piece of

Greek translation which the candidates for the scholarship have not seen

before. Of course, every candidate would be happy if he could see it before the

examination and prepare it in advance? So much care is taken to keep it secret.![]()

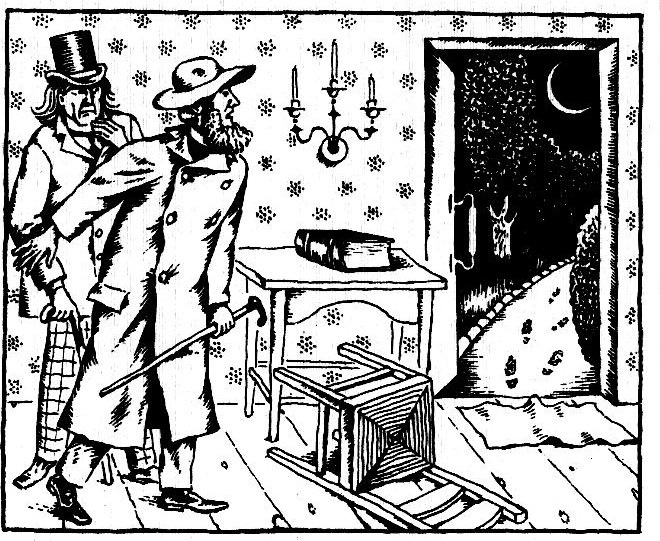

"Today at about three o'clock I was reading the proofs of the examination papers. At four-thirty I went out to take tea in a friend's room, and I left the papers upon my desk. I was absent a little more than an hour.

"When I approached my door,

I was surprised to see a key in ![]() it. For a moment I thought I had left my

own key there. But when I put my hand in my pocket, I found the key in it. The

other key to my room belonged to my servant, Bannister, who has been looking

after my room for ten years. I am absolutely sure ofhis honesty. I understood

that he had entered my room to ask if I wanted tea. When he saw I was not

there, he went out and very carelessly left the key in the door.

it. For a moment I thought I had left my

own key there. But when I put my hand in my pocket, I found the key in it. The

other key to my room belonged to my servant, Bannister, who has been looking

after my room for ten years. I am absolutely sure ofhis honesty. I understood

that he had entered my room to ask if I wanted tea. When he saw I was not

there, he went out and very carelessly left the key in the door.

"The moment I looked at my table I knew that someone had touched the examination papers. There were three pages to it. I had left them all together. Now I found that one of them was lying on the floor; one was on a small table near the window; and the third was where I had left it on my desk. "

Holmes spoke for the first time.

"The first page on the floor, the second near the wiñdow, and the third where you left it, " he repeated.

![]() "Exactly, Mr.

Holmes. But how could you know that?" ' Please, continue your very

interesting story.

"Exactly, Mr.

Holmes. But how could you know that?" ' Please, continue your very

interesting story.

the Fortescue [ ' Scholarship — CTHneHAHH VfMeHH OOPRCKbYO

2 in advance — 3apaHee

4

"I did not know what to think. Bannister said he had not touched my papers and I am sure he speaks the truth. Then I thought that some student passing by my door had noticed the key in it. Knowing that I was out, he had entered to look at the papers. The Fortescue Scholarship is a large sum of money, so the student was ready to run a risk in order to get it.

"Bannister was very much upset by the incident. He nearly fainted when I told him that someone had touched the examination papers. I gave him a little brandy and left him in a chair while I made a most careful examinationl of the room. I soon saw other traces of the man who had been in my room. Evidently the man had copied the paper in a great hurry. My writing table is quite new and I found a cut on it about three inches long. Not only this, but on the table I found a small black ball ofsomething like clay or earth, and some sawdust.

I am sure that these marks were left by the man who had touched the examination papers. But there were no traces of his footsteps. I didn't know what to do next, when suddenly the happy thought came into my head that you were in the town. So I came straight to you to put the matter into your hands.2 Do help me,3 Mr. Holmes! You see my dilemma. Either I must find the man, or4 the examination must be put off until new papers are prepared. But this cannot be done without explanations and a terrible scandal will follow. This will throw a cloud5 not only on the college but on the University. "

![]() 'l shall be happy to look into this

matter6 and give as much help as I can, " said Holmes rising and putting

on his overcoat. "The case is not without interest. 7 Did anyone visit you

in your room after the papers had come to you?"

'l shall be happy to look into this

matter6 and give as much help as I can, " said Holmes rising and putting

on his overcoat. "The case is not without interest. 7 Did anyone visit you

in your room after the papers had come to you?"

![]()

![]() I made a most careful examination — q np0H3BeJ1 caMb1M TUIaTeJ1bHb1V1

I made a most careful examination — q np0H3BeJ1 caMb1M TUIaTeJ1bHb1V1

OCMOTP

2 to put the matter into your hands — npeaocTaBHTb BaM 3aHflTbCH 3THM

3

do help me — (Tao

noMorwe xe MHe (ecn0Moeame.ThHb1ù anaeoa do ynompeõaeH ðJIR

ycu,qeHl.lH npocúbl) ![]()

4 either I must find the man, or— JIVf60 H AOJIXeH HañTH BVfHOBHHKa,

![]() 5 to throw a cloud — 6pocaTb TeHb

5 to throw a cloud — 6pocaTb TeHb

6

to look into this

matter — 3aHflTbCH 3THM![]()

7 The case i' not without interest. — Lleno AOBOJ1bHO MHTepeCHoe.

5

03HaK0MwreAbHa¶

"Yes, " said Mr. Soames. "Young Daulat Ras, an Indian student"théll, " said Holmes laughing, "ifthere is nothing to be learned who lives on the same floor, came over to ask me a question abouthere,l we had better go inside, 2" some details of the examination. "The lecturer unlocked his door and we went in.

"The examination which he is going to take?"![]() "Your

servant seems to have felt better,3" said Holmes. " He is

"Your

servant seems to have felt better,3" said Holmes. " He is

![]()

"Yes. 'not here. You left him in a chair, you say. Which chair?"

![]()

"And the papers were on your table?" " By the window over there. "

![]()

"Yes,

but as far as I remembêr, they were rolled up. ![]() 'I see. Near this

little table. Of course, what has happened is

'I see. Near this

little table. Of course, what has happened is

"Did anyone else come to your room?" quite clear. The man entered and took the papers, page by page, from

![]()

![]() "No. your

writing-table. He carried them over to the window table, because

"No. your

writing-table. He carried them over to the window table, because

"Did anyone know that the papers would be there?"

from there he could see if you came across the courtyard. " ![]() "No

one.'

"No

one.'![]() "He couldn't see me," said

Soames, "for I entered by the side

"He couldn't see me," said

Soames, "for I entered by the side

" Did this man Bannister know?" door.

"![]()

"No, certainly not. No one knew. " "Ah, that's good," said Holmes. ''Véll, he carried the first page

"Where is Bannister now?" over to the window and copied it. Then he threw it down and took

"He was very ill,

poor man! I left him in my room, I was in a![]() the next one. He was

copying it when your return made him go away hurry to come to you. " in a

hurry. 4 He had no time to put the papers back. Did you hear any

the next one. He was

copying it when your return made him go away hurry to come to you. " in a

hurry. 4 He had no time to put the papers back. Did you hear any

"So you left your door open?" hurrying steps on the stairs as you came up to your door?"

"Yes, but I locked up the papers first. " "No, I didn't."

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() "Well,

it seems, Mr. Soames, that the man who touched your "WI , " Sherlock

Holmes went on, "I don't think we can learn papers came upon them without

knowing2 that they were there. '

"Well,

it seems, Mr. Soames, that the man who touched your "WI , " Sherlock

Holmes went on, "I don't think we can learn papers came upon them without

knowing2 that they were there. '![]() anything more from this table. Let's

examine the writing table. The "So it seems to me," said Mr. Soames.

man left no traces on it except some clay and sawdust. Dear me, 5 this

"Let's go to your room now, Mr. Soames. I am at yourservice.3 is very

interesting. And the cut — I see. Where does that door lead All right, Watson,

come with us if you want to.4" to?" Holmes asked suddenly.

anything more from this table. Let's

examine the writing table. The "So it seems to me," said Mr. Soames.

man left no traces on it except some clay and sawdust. Dear me, 5 this

"Let's go to your room now, Mr. Soames. I am at yourservice.3 is very

interesting. And the cut — I see. Where does that door lead All right, Watson,

come with us if you want to.4" to?" Holmes asked suddenly.

"To my bedroom, " answered Soames.

"I should like to have a look6 at it, " said

Holmes.![]()

He entered the bedroom and examined it carefully.

![]()

It was already getting dark when we entered the courtyard of

"No, I see nothing," he said. "What about this curtain? Oh ![]() the old college. The window of our

client's sitting-room opened you hang your clothes behind it. If

anyonèhas to conceal himself in onto it. Holmes approached the window.

Then he stood on tiptoe in

the old college. The window of our

client's sitting-room opened you hang your clothes behind it. If

anyonèhas to conceal himself in onto it. Holmes approached the window.

Then he stood on tiptoe in![]() this room, he must do it there — the bed is too low. No one there, order

to look inside.

this room, he must do it there — the bed is too low. No one there, order

to look inside. ![]()

![]()

'He

must have entered5 through the door, " said Mr. Soames, ![]()

"the

window doesn't open.![]() I if there is nothing to be learned here — eCJIH HEIb3q HHqero Y'3HaTb

3Aecb

I if there is nothing to be learned here — eCJIH HEIb3q HHqero Y'3HaTb

3Aecb

2 we had better go inside — HaM JlYMLue BOMTH B AOM

3

your servant

seems to have felt better — Kaxemcq, Bam cnyra not-{YBcas far as I remember —

HaCKOJ1bKO q HOMHIO TBOBUI ce6H Jlyqu_re (cyõb•eKmHb1ù

u*HumueHb1ù 060pom)![]()

2

without

knowing — He 3Haq, He non03peBafl 4 made him go away in a hurry

— 3aCTaBW1 ero nocneLLJH0![]()

3 lam at your service. — 51 K BaUJHM ycnyraM. 5 Dear me — boxe MOW (eocKuqu1WHue, ßblpa*awtgee yòuenuue, co-

4 if you want to (come) ecnø Bbl XOTHTe (noñTH) .*a-aeHue) he must have entered — OH, oqeBHAHO, BOURJI 6 | should like to have a look — MHe XOTeÃOCb 6b1 B3rJIHHYTb

6 7

031--1aK0MwreAb1--ra¶

I suppose?" And he drew the curtain. It seemed to me that he was prepared to find somebody behind the curtain and to act quickly.

"No one," said Holmes. "But what's this?" And he picked up from the floor a small ball of black clay, exactly like the one upon the table.

"Your visitor seems to have left

traces I in your bedroom as well as in your sitting-room, " he said. ![]()

"Do you mean to tell me that he was in my bedroom? What for?" asked Mr. Soames.

"I think it is clear

enough," answered Holmes. "You came ![]() back by the side door,

while he was sure that you would come across the courtyard, so he did not see

you coming back, and he was copying the paper until he heard your steps at the

very door. What could

back by the side door,

while he was sure that you would come across the courtyard, so he did not see

you coming back, and he was copying the paper until he heard your steps at the

very door. What could

he do? He caught up everything he had with him and he rushed

into your bedroom to hide himself. " ![]()

"Good God 2 Mr. Holmes, do you mean to tell me that all the time I was talking to Bannister we had the criminal in my bedroom?"

"So I understand it.'![]()

![]() 'Perhaps he got out by

the window," began Mr. Soames, but Holmes shook his head impatiently.

'Perhaps he got out by

the window," began Mr. Soames, but Holmes shook his head impatiently.

![]() 'l think you have told me, " he said,

"that there are three students who use the stairs and pass your door.

'l think you have told me, " he said,

"that there are three students who use the stairs and pass your door.![]()

"Yes, there are. '![]()

"And they are all going to take the examination?"

"Yes. '![]()

"Who are they?" asked Holmes.

"The first floor, " began Soames, "is occupied by a fine student and athlete, he plays cricket for the college3 and is a prize-winner for the long jump 4 He is a fine young fellow. His father was very rich,

your visitor seems to have left traces — Baul noceTHTeJ1b, KaxeTCH,

OCTaBHA CJ1eAb1![]()

2 Good God — 60xe MWIOCTMBb1ñ

3 he Plays cricket for the college — OH urpaer B KPHKeT B KOMaHAe KOJI-neaxa

4

a prize-winner for the long jump — n06eAMTeJ1b B COPeBHOBaHHflX no

11Pb1XKaM B![]()

8

en is .ru but lost all his money

in horse-racing. He died, and young Gilchrist was left very poor. But he is

hard-working and will do well.l ![]()

"The second floor," continued Mr. Soames, "is occupied by Daulat Ras, the Indian. He is a very quiet fellow, very hard-working too, though his Greek is his weak subject.

"The top floor belongs to Miles McLaren. He is a brilliant fellow when he wants to work — one of the brightest intellects of the University. But his conduct is very bad. He was nearly expelled because of a card scandal in his first year.2 He is very lazy and I am sure very much afraid of the examination. Perhaps of the three he is the only one3 who might possibly be suspected/"

![]() "Exactly, "

said Holmes. "Now, Mr. Soames, let us have a look at your servant,

Bannister.'

"Exactly, "

said Holmes. "Now, Mr. Soames, let us have a look at your servant,

Bannister.'

![]() Bannister was a little, white-faced,

clean-shaven, grey-haired fellow of fifty. His hands were shaking, he was so

nervous.

Bannister was a little, white-faced,

clean-shaven, grey-haired fellow of fifty. His hands were shaking, he was so

nervous.

![]() 'I understand," began Holmes,

"that you left your key in the

'I understand," began Holmes,

"that you left your key in the

![]()

"Yes, sir. '

"Was it not rather strange that you should do this on the very day-5 when there were these papers inside?"

"It was most unfortunate, sir. But I have done the same thing at other times. "

"When did you enter the room?"

![]() 'It was about half past four. That is Mr. Soames's tea-time. "

'It was about half past four. That is Mr. Soames's tea-time. "

" How long did you stay?"

"When I saw that he was out I left at once.'![]()

![]() 'Did you look at the papers on the

table?"

'Did you look at the papers on the

table?"

![]()

"No, sir, certainly not.'

"How did it happen that you left the key in the door?"![]()

![]() I had the tea-tray in my hand. I thought I would come back for the key.

Then I forgot."

I had the tea-tray in my hand. I thought I would come back for the key.

Then I forgot."

"Then the door was open all the time?"

will do well — 6yaeT npeycrreBaTb (B XM3HM)

2 in his first year — Ha nepBOM Kypce

3 perhaps of the three he is the only one — B03MOXHO, 1,13 TPOMX CT'YIRHTOB OH eaHHCTBeHHb1ñ

4 who might possibly be suspected — Koro MOXHO 3ar10A03pMTb

5 on the very day — B TOT CaMbIÜ AeHb

9

03HaK0MwreAbHa¶

"Yes, sir. '![]()

"When Mr. Soames returned and sent for you, you were very much upset?"

![]() "Yes, sir. I nearly fainted,

sir."

"Yes, sir. I nearly fainted,

sir."

"Where were you when you began to feel bad?"

![]()

"Where was l, sir? Why, I here, near the door.'

"That is strange, because you sat down in that chair near the window. Why did you pass these other chairs?"

"I don't know, sir. It did not matter to me where I sat."

"I really don't think he knew much about it, Mr. Holmes. He

looked very bad, " said Mr. Soames.

"You stayed here when your master left?" went on Holmes.

"Only for a minute or so. Then I locked the door and went to my room. "

"Whom do you suspect?"

![]()

"Thank you, that will do,2"

said Holmes. "And now, Mr. Soames, I should like to have a look at the

three students. Is it possible?" ![]()

"No difficulty at

all," answered Soames. "Visitors often go over the college3. Come

along. I shall be your guide." ![]()

"No names,4 please,"

said Holmes, as we knocked at Gil- ![]() christ's door. A tall young fellow opened

the door and very politely invited us into the room. The student left a very

pleasant impression. The Indian, a silent little fellow seemed to be very glad5

when we said

christ's door. A tall young fellow opened

the door and very politely invited us into the room. The student left a very

pleasant impression. The Indian, a silent little fellow seemed to be very glad5

when we said

good-bye to him. did not get into the third room. In answer to our knock nothing but bad language6 came from behind the door.

"I don't care7 who you are. You can go to the devil," roared the angry voice. "Tomorrow is the exam, and I won't open my door to anyone"'

![]()

I why — HY, H Jaywao

2 that will do — 110CTaTOHHO, BCe go

over the college — ![]() Konneax

Konneax

![]() 4 no names — He Ha3b1BaHTe HaU_1HX

HMeH seemed to be very glad — Ka3a•10Cb, OqeHb 06pa.A0Bancq

4 no names — He Ha3b1BaHTe HaU_1HX

HMeH seemed to be very glad — Ka3a•10Cb, OqeHb 06pa.A0Bancq

6 bad language — pyraHb, 6paHb

![]() I don't care — MHe HarureBaTb

I don't care — MHe HarureBaTb

![]()

I won't open my door to anyone — q He c06HpaIOCb HHKOMY OTKPb1BaTb

ABepb

![]() 10

10

"A rude fellow," said our guide turning red with anger, "of

course, he did not know who was knocking, but anyhow his

conduct is rather suspicious. "![]()

Holmes' reply was indeed strange.

"Can you tell me his exact height?" he asked.

"Really, Mr. Holmes," answered Soames in surprise, "l can't. He is taller than the Indian, not so tall as Gilchrist. "

"That is very important, " said Holmes.

"And now, Mr. Soames, I wish you good night." ![]()

![]() "Good God, Mr.

Holmes, are you going to leave me in this terrible situation?" cried Mr.

Soames. "Tomorrow is the examination. I must take some definite action

tonight. "

"Good God, Mr.

Holmes, are you going to leave me in this terrible situation?" cried Mr.

Soames. "Tomorrow is the examination. I must take some definite action

tonight. "

"You must leave things as they are. I shall come early tomorrow morning and we shall talk the matter over. I hope that I shall be able to help you. Meanwhile you change nothing — nothing at all.

Good-bye. "

'Avery good, Mr. Holmes, good-bye.'![]()

"théll, Watson, what do you think of it?" Holmes asked, as we came out into the street. "There are three men. It must be one of them. What is your opinion?"

![]() "The rude fellow on the top floor

made the worst impression, but that Indian looked at us in a queer way, l"

I remarked.

"The rude fellow on the top floor

made the worst impression, but that Indian looked at us in a queer way, l"

I remarked.

" So would you2 ifa group

ofstrangers came in on you when you were preparing for an examination next

morning. No, I see nothing in it. But that fellow Bannister does puzzle me.![]()

![]() 'He impressed me as a perfectly honest

man," I said.

'He impressed me as a perfectly honest

man," I said.

"So he did me.4 That's all very puzzling. should a perfectly honest man?. "5 Holmes stopped and did not say a word more about the case the whole evening.

in a queer way — CTPaHHO

SO would you — H Bbl 6b' TaK xe CMOTPeJIM

3 does puzzle me — KaK pa3 cMYIuaeT Meh-{q (uaeo,q does òaH ònq ycuneH10

3HayeHun OCH08HœO aqaeona)

4 So he did me. — TaKoe xe BneqaTJ1ewe FIPOH3BeJ1 OH H Ha MeHq.

5 Why should a perfectly honest man?.. — 3aqeM 6b] trecTHOMY qeJIOBeKY?..

11

03HaK0MwreAbHa¶

At eight in the morning Holmes came into my room.

"WI, thâtson, " said he, "it is time we went down to the college. I

Soames will be in a terrible state until we tell him something positive.

'![]()

![]() 'Have you got anything positive to tell

him?"

'Have you got anything positive to tell

him?"![]()

![]() "WI, my dear Watson, I have solved the mystery. "

"WI, my dear Watson, I have solved the mystery. "

"Have you got fresh evidence?"

"Aha! It is not for nothing that I got up at six2 and covered at least3 five miles in two hours. Look at that!"

He held out his hand and I saw three little balls of black

clay. "Why, Holmes, you had only two yesterday. '![]()

![]() "And one more this morning.

Don't you think, Watson, that the source of No 3 is also the source of Nos4 1

and 2? Eh, Watson?

"And one more this morning.

Don't you think, Watson, that the source of No 3 is also the source of Nos4 1

and 2? Eh, Watson?

Well, come along and let us help Mr. Soames out of his trouble. "

We found Mr. Soames in a very nervous state. He ran towards Holmes.

"Thank heaven, you have come! I feared that you had given up the case in despair.5 What am I to do?6 Shall we begin the exami-

![]()

"Yes, of course, let it begin.![]()

"But this rascal?"

![]()

"He will not take the examination.

"You know him?"

"l think so. Kindly ring the bell."

Bannister entered and stepped back in surprise and fear when he saw Holmes again,

![]()

it is time we went down to the college — nopa OTHPaBHTbCfl B KOJL1e11X

( nocqe 060poma it is time ynompeõuemcg cocaaeament,Haq ØopMa azaeona,

8 ÒaHHOM cayqae went.)

2 it is not for nothing that I got up at six — He 3P51 xe q BCTWI B 6 HacoB

yrpa

3 and covered at least — H npol_nearr neu1KOM no KpaüHeü Mepe

4 Nos — H0Mepa

5 you had given up the case in despair — OTKa3aJIHCb paccneAOBaTb 3TO aeno KaK 6e3Haae*Hoe

6 "mat am I to do? — LITO H UOJIXeH aenaTb? (Thaeon to be c UHØUHUmueoM oõ03Haqaem òomyceHcmgoeaHue.)

![]() 12

12

"Will you please tell me, Bannister,

" began Holmes,"the truth about yesterday's incident?" ![]()

![]() The man turned white to the roots of his

hair.

The man turned white to the roots of his

hair.

![]() 'I have told you everything, sir, "

he said.

'I have told you everything, sir, "

he said.

"Nothing to add?"

![]()

"Nothing at all, sir.'

S'WI, then I shall help you. When you sat down on that chair at the window, did you do so in order to conceal some object? An object which could have shown I Mr. Soames who had been in the room?" Bannister's face was deathly pale.

![]() "No, sir, certainly not."

"No, sir, certainly not." ![]()

"Oh, it is only a suggestion,

" said Holmes very politely. "I can't prove it. But it seems probable

enough that when Mr. Soames left the room you let out the man who had been

hiding in that bedroom. " Bannister licked his dry lips.![]()

![]()

"There was no man, sir.

"Come, come 2 Bannister.'![]()

"No, sir, there was no one. "

"All right, then that will do. But please remain in the room, Bannister. Now, Soames, may I ask you to go up to the room of young

Gilchrist and ask him to step down into yours?"

A moment later Soames returned, bringing

with him the ![]() He was tall and very handsome, with a

pleasant open face. His troubled blue eyes glanced at each of us, and finally

rested on Bannister.

He was tall and very handsome, with a

pleasant open face. His troubled blue eyes glanced at each of us, and finally

rested on Bannister.

"Now, Mr. Gilchrist, we are all quite alone here, no one will ever know a word ofwhat passes between us. want to know, Mr. Gilchrist, how you, an honest man, could do such a thing as you did yesterday. "

The young man looked at Bannister with horror and reproach.

"No, no, Mr. Gilchrist, " cried

the servant. "I never said a word. '![]()

" But you have now, "3 cried Holmes. "Now, Mr. Gilchrist, you must see that your position is hopeless. Your only chance is a frank confession. "

which could have shown — KOTOPb1Vi Mor 6bI BblAaTb (õYK8. rt0Ka3aTb)

![]() 2

2

come, come — HY, nom-10, ycnoK0ÈiTecb

3 But you have (said) now. — Ho Bbl rlPOM3HeCJIH ceüqac.

13

For a moment Gilchrist tried to say something but suddenly

![]()

he burst into a storm of sobbing. I ![]()

![]() "Come, come," said Holmes

kindly. "We know that you are not a criminal. Don't trouble to answer. I

shall tell Mr. Soames what happened, and you listen and correct me where I am

wrong.

"Come, come," said Holmes

kindly. "We know that you are not a criminal. Don't trouble to answer. I

shall tell Mr. Soames what happened, and you listen and correct me where I am

wrong.![]()

" From the moment you told me your story, Mr. Soames, it was clear to me that the man who entered your room knew that the papers were there. How did he know? You remember, of course, that I examined your window. I was thinking of how tall a man must be in order to see, as he passed, what papers were on the writing-table. I

am six feet high2 and I could do it with an effort. So, I had reason to think that only a man of unusual height could see the papers through the window.

![]() 'I entered your room, Mr. Soames, and

still could make nothing of3 all the evidence, until you mentioned that

Gilchrist was a long-distancejumper.4 Then the whole thing came to me at once

and I only needed some additional evidence, which I got very soon.

'I entered your room, Mr. Soames, and

still could make nothing of3 all the evidence, until you mentioned that

Gilchrist was a long-distancejumper.4 Then the whole thing came to me at once

and I only needed some additional evidence, which I got very soon.

"What happened was this. This young fellow had spent his afternoon at the sports ground, where he had been practising the

jump. He returned carrying his jumping shoes, the soles of which, as you know very well, have spikes in them. As he passed your window, he saw, by means of his great height, these papers on your writing-table and understood what they were. No harm would have been done had he not noticed the key6 left in the door by the carelessness of your servant. A sudden impulse made him enter your room and see if they were indeed the examination papers. It was not a dangerous action: he could always pretend that he had simply come in to ask a question.

![]()

I burst into a storm of sobbing — pa3pa3HJ1cq OTqaHHHb1MM Pb1AaHH-

2 | am six feet high — MOM POCT URCTb (þYTOB

3 still could make nothing of — BCe eule He Mor caenaTb BblBOna 1-13

4

a long-distance jumper — cnop-rcMeH, cneuwa-%f3Hpyžouutñcfl no

![]() npb1*KaM B

npb1*KaM B![]()

5 by means of — 6naronapq

6 no harm would have been done had he not noticed the key — He 3',weTb OH WII-OH, HHqero aypHoro He rlPOH30LWIO 6b1 (cocqaeament,'toe HawlOHeHUe e ycJ106H0M npeð/10*eHuu mpemæeo muna)

14

![]() "

"*éli, he forgot his honour, when he saw the Greek text for the

examination. He put his jumping shoes on the writing-table. What was it you put

on that chair near the window?"

"

"*éli, he forgot his honour, when he saw the Greek text for the

examination. He put his jumping shoes on the writing-table. What was it you put

on that chair near the window?" ![]() "Gloves, " answered the young

man.

"Gloves, " answered the young

man.

Holmes looked at Bannister in triumph.

![]() 'He put his gloves on the chair, "

went on Holmes, "and he took the examination papers, page by page, to the

window table to copy them. He was sure that Mr. Soames would return by the main

gate, and that he would see him. As we know, he came back by the side gate.

Suddenly he heard Mr. Soames at the very door, There was no way by which he

could escape. He forgot to take his gloves, but he caught up his shoes and

rushed into the bedroom. The cut on the desk is slight at one side, but deeper

in the direction of the bedroom door. That is enough to show us the direction

in which he drew the shoes. Some of the clay round the spike was left on the

desk and a second ball of clay fell in the bedroom.

'He put his gloves on the chair, "

went on Holmes, "and he took the examination papers, page by page, to the

window table to copy them. He was sure that Mr. Soames would return by the main

gate, and that he would see him. As we know, he came back by the side gate.

Suddenly he heard Mr. Soames at the very door, There was no way by which he

could escape. He forgot to take his gloves, but he caught up his shoes and

rushed into the bedroom. The cut on the desk is slight at one side, but deeper

in the direction of the bedroom door. That is enough to show us the direction

in which he drew the shoes. Some of the clay round the spike was left on the

desk and a second ball of clay fell in the bedroom.

![]() "I walked out to the sports ground

this morning and saw that black clay is used in the jumping pit. I carried away

some of it, together with some sawdust, which is used to prevent the athletes

from slipping.l Have I told the truth, Mr. Gilchrist?"

"I walked out to the sports ground

this morning and saw that black clay is used in the jumping pit. I carried away

some of it, together with some sawdust, which is used to prevent the athletes

from slipping.l Have I told the truth, Mr. Gilchrist?" ![]() "Yes,

sir, it is true," said he.

"Yes,

sir, it is true," said he.

"Good heavens, have you got nothing to add?" cried Soames.

![]() "Yes, sir, I

have. I have a letter here which I wrote to you early this morning after a

restless night. Of course, I did not know then that my action was known to

everyone. Here it is 2 sir. You will see that I have written, 'I have decided

not to take the examination. I have found some work and I shall start working

at once.'

"Yes, sir, I

have. I have a letter here which I wrote to you early this morning after a

restless night. Of course, I did not know then that my action was known to

everyone. Here it is 2 sir. You will see that I have written, 'I have decided

not to take the examination. I have found some work and I shall start working

at once.'

![]() "I am, indeed, pleased to hear that

from you, Gilchrist, " said Soames. "But why did you change your

plans?"

"I am, indeed, pleased to hear that

from you, Gilchrist, " said Soames. "But why did you change your

plans?" ![]()

"There is the man who sent me in the right path," said the student, pointing to Bannister.

"Come, now, Bannister," said Holmes. "It is clear now to all of us that only you could have let this young man out, since you were

to prevent the athletes from sl$ping — He aaTb

crIOPTCMeHaM fiOCKOJ1b3HYTbcH ![]()

2 here it is — BOT OHO

15

leftin the room alone. That is quite clear. What is not quite clear is

the reason for your action. '![]()

![]() "The reason was

simple enough, " answered Bannister. " Many years ago I was a butler

in the house ofthis young gentleman's father. When he died I came to the

college as a servant, but I never forgot the family. WI, sir, as I came into

this room yesterday, when Mr. Soames was so much upset, the first thing I saw

was Mr. Gilchrist's gloves lying in that chair. I knew those gloves well, and I

understood immediately what they meant. If Mr. Soames saw them, Gilchrist would

certainly be a lost man. I I sat down in that chair pretending that I felt very

bad

"The reason was

simple enough, " answered Bannister. " Many years ago I was a butler

in the house ofthis young gentleman's father. When he died I came to the

college as a servant, but I never forgot the family. WI, sir, as I came into

this room yesterday, when Mr. Soames was so much upset, the first thing I saw

was Mr. Gilchrist's gloves lying in that chair. I knew those gloves well, and I

understood immediately what they meant. If Mr. Soames saw them, Gilchrist would

certainly be a lost man. I I sat down in that chair pretending that I felt very

bad ![]() When Mr. Soames went to you, Mr. Holmes,

my poor young master came out ofthe bedroom and confessed it all to me. Wasn 't

it natural, sir, that I should save him 2 and wasn't it natural also that I

should speak to him like a father and make him understand that he must not

profit by such an action? Can you blame me, sir?"

When Mr. Soames went to you, Mr. Holmes,

my poor young master came out ofthe bedroom and confessed it all to me. Wasn 't

it natural, sir, that I should save him 2 and wasn't it natural also that I

should speak to him like a father and make him understand that he must not

profit by such an action? Can you blame me, sir?"![]()

"No, indeed, " said Holmes heartily, jumping to his feet. "WI, Soames. I think we haye cleared your little problem up, and our breakfast awaits us at home. Come, Watson! As to you 3 Mr. Gilchrist, I hope a bright future awaits you. For once4 you have fallen low. Let us see in the future how high you can rise. "

![]() Comprehension Check

Comprehension Check

1. Say who in the story:

l) was so excited that it was clear that something very unusual had happened.

2) agreed to listen to the visitor's story, though very unwillingly.

would... be a lost man — Hero 6b1JIO 6bI BCe KOHqeHO

2 wasn't it natural... that I should save him — 3ò. pa3Be Mor q... He crracTH ero

3

as to you — I-ITO Kacaemcq Bac

4 for once — B 3TOT pa3

16

3) would be happy if he could see the examination papers in advance.

![]() 4) was very much upset by the incident.

4) was very much upset by the incident.

5) would be happy to look into the matter and give as much help as he could.

6)

used the same stairs and passed the professor's door.![]()

7) made the worst impression on Watson.

8) looked at the unexpected visitors in a queer way.

9)

entered and stepped in surprise and fear when he saw Holmes

again. ![]()

10) looked-at Bannister with horror and reproach.

I l) tried to say something but suddenly burst into a storm of sobbing.

12) had written the following: "I have decided not to take the examination. I have found some work and I shall start working at once. "

2. Say who in the story said it and in connection with what.

I) "I am very busy now. Could you call the police?"

2)

![]() 'l am sure you will keep our secret. You

are the only man in the world who can help me."

'l am sure you will keep our secret. You

are the only man in the world who can help me."

3) "The Fortescue Scholarship is a large sum of money, so the student was ready to run a risk in order to get it. "

4) "The case is not without interest. "

![]() 5) "He must have

entered through the door. The window doesn't open. '

5) "He must have

entered through the door. The window doesn't open. '![]()

6)

![]() ..Mr. Holmes, do you mean to tell me that

all the time I was talking to Bannister we had the criminal in my bed-

..Mr. Holmes, do you mean to tell me that

all the time I was talking to Bannister we had the criminal in my bed-

7)

![]() '"His father was very rich, but lost all his money in

horseracing.'

'"His father was very rich, but lost all his money in

horseracing.'

8) "He is very lazy and I am sure very much afraid of the examination."

![]()

9) "No names, please.

10) " But that fellow Bannister does puzzle me. "

11) "I feared that you had given up the case in despair. "

12) " Gloves. "

17

13) "I

have a letter here which I wrote to you early this morn![]() ing after a restless

night. "

ing after a restless

night. "

14) "For

once you have fallen low. Let us see in the future ![]() how high you can rise.

"

how high you can rise.

"

3. Say true, false or I don't know.

l ) One evening Watson and Holmes received a visit from a certain student.

2) It was one of the cases when it was necessary to avoid scandal.

3) The next day was the first day of the examination for the Soros Scholarship.

4) The first of the papers consisted of a piece of a Latin translation.

5)

When the lecturer entered the room, he knew that someone had

touched his papers. ![]()

6) He thought that it was Bannister who had messed them up.

7) Bannister was very much upset by the incident.

8) Mr. Soames' writing-table was quite new and there were no scratches on it after the incident.

9)

Five students shared the same building with Mr. Soames and passed

his door, using the same stairs. ![]()

10) Mr.

Soames suspected none of them to have touched the examination papers.![]()

I l) All the three students were very agreeable young people.

12) The criminal, who had touched the papers, left no traces whatever.

13) Holmes thought the case not interesting at all and gave it up.

14) Gilchrist committed this crime with cold heart and wasn 't sorry about it.

15) In

the future Gilchrist will rise high. ![]()

4. Answer the following questions.

l) Where did Mr. Sherlock Holmes and doctor Watson spend several weeks?

18

![]()

![]()

![]() 1.

1.

2) Who paid them a visit one evening?

3) Why was it so important for Mr. Soames to avoid scan-

dal?

4) Why much care was taken to keep the examination papers secret?

5) What did Mr. Soames find when he entered his sittingroom one day?

6) Nobody had touched the examination papers, had they?

![]()

7) Who else was greatly upset by the incident?

8)

![]() Wasn't it rather strange that Bannister

had left the key in the door on the very day these papers were inside?

Wasn't it rather strange that Bannister

had left the key in the door on the very day these papers were inside?

9)

![]() all the students, living in the same house

with Mr. Soames, reliable young men or did they arouse suspicion?

all the students, living in the same house

with Mr. Soames, reliable young men or did they arouse suspicion?

10) When being asked by Sherlock Holmes, Bannister was absolutely calm and reserved, wasn't he?

I l) When examining the crime scene Sherlock Holmes found no evidence, did he?

12) Why did Gilchrist's eyes finally rest on Bannister, when Mr. Soames invited him to his room?

13) Why did the student burst into a storm of sobbing when Holmes asked him to make a frank confession?

14) What

clues did Holmes get when he examined Soames' room and the sports grounds? ![]()

15) What made him think that the criminal was an athlete?

16) Why was old Bannister covering the young man?

17) Why does Holmes say at the end ofthe story that "a bright future" awaits Mr. Gilchrist?

18) Do you despise young Gilchrist for what he did or do you feel sorry for him? Why?

Working with the Vocabulary

Choose to use as, like, as as in the following sentences. Before doing the exercise, consider the examples and set phrases given below.

19

03HaKOM1-rreAbHa¶

Examples Set phrases

|

The girl is like a rose. |

such as |

|

He did, as I asked him to do. |

as to (for) me |

|

He worked as (a) gardener. |

as usual |

|

She is as cold as ice. |

as far as I know |

as well as

1) 'I shall be happy to look into this matter and give such

help I can," said

Holmes.![]()

2)

"Yes, but I remember, they were rolled up." ![]()

3)

"You must leave things![]() they are."

they are."

4) "Your visitor seems to have left traces in your bedroom

well your sitting-room, " he said.

5)

![]()

![]() 'He impressed me a

perfectly honest man," I said.

'He impressed me a

perfectly honest man," I said.

6)

![]() "We want to know, Mr. Gilchrist, how you, an honest

man, could do such a thingyou did yesterday. "

"We want to know, Mr. Gilchrist, how you, an honest

man, could do such a thingyou did yesterday. "![]()

7)

"He returned carrying his jumping shoes, the soles of which,![]() you know very

well, have spikes.

you know very

well, have spikes.![]()

8) "When he died, I came to the college a servant,

![]()

but I never forgot the family. "

9)

"Wasn't it natural that I should speak to him![]() a

a

10)

to you, Mr. Gilchrist, I hope a bright

future

to you, Mr. Gilchrist, I hope a bright

future

awaits you.

2. Consider the following prepositional phrases, picked out from the story•

a)

Translate them

into Russian. ![]()

To consist of; in advance; to look after; to be sure of; to look into the matter; to come upon; to stand on tiptoe; to look at; to send for; in answer to; to turn red with rage (anger); in a queer way; to give up; in surprise; in despair; to burst into; by means of; to prevent smb from; a reason for; to clear up; a key

b) ![]()

![]() Complete the sentences below with

appropriate prepositions.

Complete the sentences below with

appropriate prepositions.

I) "Thank heaven, you have come! I feared that you had ![]() given

given![]() the

case despair. "

the

case despair. "

![]()

2)

For a moment Gilchrist tried to say something but suddenly he

burst![]() a storm of sobbing.

a storm of sobbing.

3)

Bannister entered and stepped back ![]() surprise and fear when

he saw Holmes again.

surprise and fear when

he saw Holmes again.

4)![]() "When Mr. Soames returned and sent

"When Mr. Soames returned and sent ![]() you,

were

you,

were

you very much upset?"

5)

"A rude fellow, " said our guide turning red![]() anger.

anger.

6)

The first ofthe examination papers consists![]() a piece

a piece

of Greek translation.

![]()

7)

![]() 'I shall be happy to look

'I shall be happy to look![]() this matter

and give such help as I can, " said Holmes, rising.

this matter

and give such help as I can, " said Holmes, rising.

![]()

8)

![]() Holmes approached the window. Then he stood up tiptoe in

order to look inside.

Holmes approached the window. Then he stood up tiptoe in

order to look inside.

9)

"Well, it seems, Mr. Soames, that the man who touched your

papers came![]() them without knowing that they were there.

"

them without knowing that they were there.

"

10)

answer![]() our knock nothing but bad language

our knock nothing but bad language

![]()

came from behind the door.

![]()

11)

![]() "As he passed the window, he saw,

"As he passed the window, he saw, ![]() means

means ![]() his

great height, these papers on your writing-table.

his

great height, these papers on your writing-table.

12)

Holmes looked![]() Bannister triumph.

Bannister triumph.

![]()

12)

"What is not quite clear is the reason your ac![]() tion.'

tion.'![]()

13)

![]() "l carried away some sawdust, which is used to

prevent the athletes

"l carried away some sawdust, which is used to

prevent the athletes![]() slipping.

slipping.

14)

"Well, Soames, I think we have cleared your little problem

and our breakfast awaits us at home. " ![]()

15)

"Really, Mr. Holmes," answered Soames ![]() surprise.

surprise.

16)

"The other key ![]() my room belongs to my servant, Bannister,

who has been looking my room for ten years. "

my room belongs to my servant, Bannister,

who has been looking my room for ten years. "

17)

"Let's go to your room now, Mr. Soames. I am ![]()

![]()

to a room; to be at one's service. your service. '

20 21

03HaK0MwreAbHa¶

c) Make up your own sentences with some of these prepositional phrases.

3. a) Mate the words and phrases in the left-hand column with their definitions in the right-hand column.

l ) to avoidto prevent smth from

happening

l ) to avoidto prevent smth from

happening

2) in advanceto hide oneself

3) to run a riska very difficult situation; a hard task to solve

5) to look into a matterto dismiss officially from school, college

6) to approachto look in a strange, unnatural way

7) to conceal oneselfto start doing

8)

to expel ![]() to face danger

to face danger

9)

That will do.![]() ahead; beforehand

ahead; beforehand

10) to

take some actionto reach; to come closer ![]() to look in a queer way

to investigate the matter

to look in a queer way

to investigate the matter

12)

a lost man ![]() to get (gain) advantage from

to get (gain) advantage from

13)

to profit bya man without any hope or future![]()

14) to put offto move to a later date; to delay

b)

Complete the following sentences from the story with the phrases or ![]() their elements from the left-hand

column (in an appropriate form). l) "Thank you. " said Holmes.

their elements from the left-hand

column (in an appropriate form). l) "Thank you. " said Holmes.

2)

"Tomorrow is the examination. I must![]() tonight. "

tonight. "

3)

If anyone has to![]() himself in this room, he must do it here —

the bed is too low.'

himself in this room, he must do it here —

the bed is too low.'![]()

![]() 4) 'But his conduct is very bad. He

was nearly

4) 'But his conduct is very bad. He

was nearly ![]() because of a card scandal in his first year. "

because of a card scandal in his first year. "

5) 'l shall be happy to and give such help as I can,"

6)

![]() "You see my Either I must find the

man, or the examination must be until new papers are prepared. " 7) Holmes

"You see my Either I must find the

man, or the examination must be until new papers are prepared. " 7) Holmes![]() the

window.

the

window.

8)

It is just one of the cases when it is quite necessary ![]() scandal.

scandal.

9)

"Of course, every candidate would be happy if he could see

it before the examination and prepare it![]()

10) The

Fortescue Scholarship is a large sum of money, so the student was ready to![]() in

order to get it. "

in

order to get it. "

I l) "The rude fellow on the top floor made the worst

impression, but that Indian looked at us![]()

12) "Wasn't it also

natural that I should speak to him like a father and make him understand that

he must not ![]() such an action?"

such an action?"

4. Complete the following sentences with the words below in an appropriate form.

To confess; evidence; additional evidence; a frank confession; one's position is hopeless; a case; fresh evidence; a criminal; to be suspected; to blame somebody (for); an incident; to examine the room; to solve the mystery.

I) ![]() 'Bannister was very much upset by the

'Bannister was very much upset by the![]()

![]()

2) "Theis not without interest. '

![]()

3) "Mr. Holmes, do you mean to tell me that all the time I was talking to Bannister we had the in my bedroom?"

4) "théll, my dear Watson, I

"Have you got

5)

![]() "Your only chance is a

"Your only chance is a

6) "Now, Mr. Gilchrist, you must see that

7)

![]()

![]() "I entered your

room, Mr. Soames, and still could make nothing ofall theuntil you mentioned

that Gilchrist was a long-distance jumper. Then the whole thing came to me at

once and I only needed some which I got very soon. "

"I entered your

room, Mr. Soames, and still could make nothing ofall theuntil you mentioned

that Gilchrist was a long-distance jumper. Then the whole thing came to me at

once and I only needed some which I got very soon. "

|

said Holmes. to me. 22 23 |

8)

"When Mr. Soames went to you, Mr. Holmes, my poor young

master came out of the bedroom and![]() all 03HaK0MwreAbHa¶

all 03HaK0MwreAbHa¶

![]()

9)

"Wasn't it natural that, sir, that I should save him? Can

you![]() me, sir?"

me, sir?"![]()

10)

"He is very lazy and I am sure very much afraid of the

examination. Perhaps of the three he is the only one who might possibly![]()

![]() Discussion

Discussion

![]() Give

sketch-portraits ofthe characters ofthis story (Sherlock Holmes; Mr. Soames;

the three students — young Gilchrist, Daulat Ras, the Indian, Miles McLaren;

Bannister, Mr. Soames' servant).

Give

sketch-portraits ofthe characters ofthis story (Sherlock Holmes; Mr. Soames;

the three students — young Gilchrist, Daulat Ras, the Indian, Miles McLaren;

Bannister, Mr. Soames' servant).

2. Who did you suspect at first? How and why did your opinion change?

3.

Draw the layout of Soames's flat and explain what happened there,

making use of your plan![]()

4. Follow Holmes's train of thoughts and say what clues helped him to solve the mystery.

5. Comment on the following words:

a)

"As to you, Mr. Gilchrist, I hope a bright future awaits

you. For once you have fallen low. Let us see in the future how high you can

rise.'![]()

b) "You see my dilemma. Either I must find the man, or the examinations must be put off until new papers are prepared. But this can not be done without explanations and a terrible scandal will follow. This will throw a cloud not only on the college but on the University. "

6. What measures would be taken at your college or University, if a similar situation happened there?

7. Comment on the following proverb.

" Don't put off

till tomorrow what can be done today. ' ![]() Can it be applied to the story in

question?

Can it be applied to the story in

question?

![]() 8. Try to recall any

criminal case, describing it by means of the words and phrases from Ex. 4. How

was it solved?

8. Try to recall any

criminal case, describing it by means of the words and phrases from Ex. 4. How

was it solved?

![]()

9. Would you like to make a career of a private detective? Are you fit for it? What qualities and traits of character are required ofa detective?

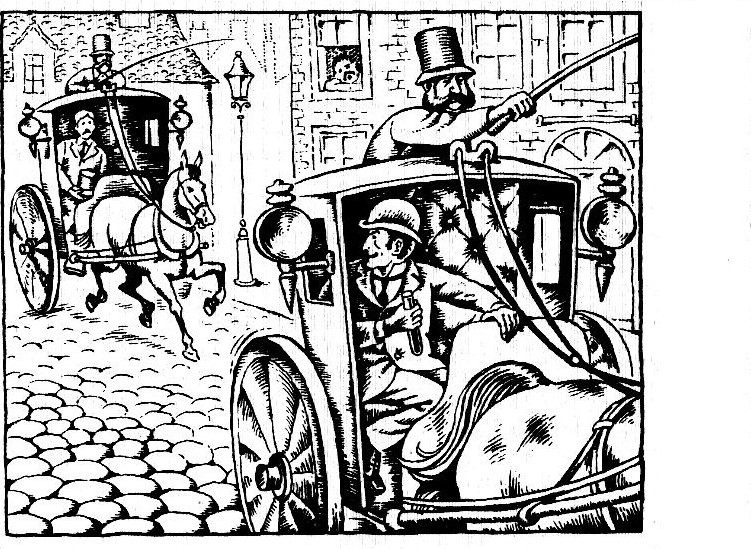

"All aboard?" I asked the Captain.

"All aboard, sir, " said the mate.

"Then stand by to let her go.2![]()

It was nine o'clock on Wednesday morning. Everything was prepared for a start. The whistle had sounded twice, the final bell had rung. The bow was turned toward England, and all was ready for Spartan's run of three thousand miles.

"Time is up!"3 said the Captain, closing his chronometer and putting it in his pocket.

![]()

I All aboard? — nocaAKa 3aKOHqeHa? (cuataq K omnnwnzwo) 2 stand by to let her go — npurOTOBMTbCfl K OTW1bITHK) 3 Time is up! — nopa OT11PaBJ1¶TbCq!

25

![]() 03HaK0MwreAb1--1a¶

03HaK0MwreAb1--1a¶ ![]() Suddenly

there was a shout from the bridge, and two men ap

Suddenly

there was a shout from the bridge, and two men ap![]() peared, running very

quickly down the quay. It was clear they were hurrying to the ship and wanted

to stop her.

peared, running very

quickly down the quay. It was clear they were hurrying to the ship and wanted

to stop her. ![]()

![]()

![]() "Look sharp!?' I shouted the people on

the quay.

"Look sharp!?' I shouted the people on

the quay.

"Ease her!2 Stop her!" cried the Captain.

![]() The two men jumped

aboard at the last moment, and the ship left the shore quickly.

The two men jumped

aboard at the last moment, and the ship left the shore quickly.![]()

The people on the quay shouted with

excitement, so did the passengers. 3 They were all glad that the two men had got

on. ![]()

![]() I went around the deck, looking at the

faces of my fellow-passengers. I found nothing interesting. Twenty types of

young Americans going to "Yurrup" 4 a few respectable middle-aged

couples, some young ladies...

I went around the deck, looking at the

faces of my fellow-passengers. I found nothing interesting. Twenty types of

young Americans going to "Yurrup" 4 a few respectable middle-aged

couples, some young ladies...

I turned away from them and looked back

at the shores of America. I wanted to be alone. So I found a place behind a

pile of suitcases and sat down on a coil of rope. I enjoyed being alone.![]()

![]()

A few minutes passed. Then I heard a whisper behind me.

![]() "Here's a quiet place, " said a

voice. "Sit down and we can talk it over. Nobody can overhear us here.

"

"Here's a quiet place, " said a

voice. "Sit down and we can talk it over. Nobody can overhear us here.

"

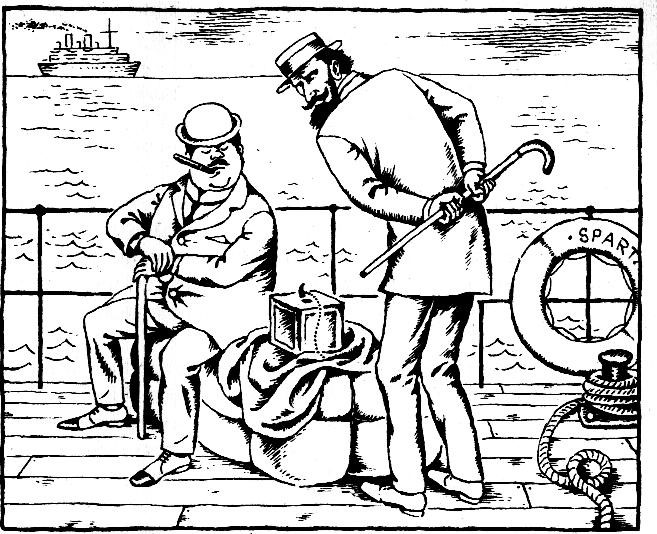

![]() The pile of suitcases

was between the men and myself. Looking through a chink between two big

suitcases I saw that they were

The pile of suitcases

was between the men and myself. Looking through a chink between two big

suitcases I saw that they were ![]() the passengers who had joined us at the

last moment. I was sure they did not see me. The one who had spoken was a tall,

thin man with a blue-black beard and a colourless face. His companion was a

short fellow. He had a cigar in his mouth and a coat hung over his arm.

the passengers who had joined us at the

last moment. I was sure they did not see me. The one who had spoken was a tall,

thin man with a blue-black beard and a colourless face. His companion was a

short fellow. He had a cigar in his mouth and a coat hung over his arm. ![]() They

both looked around them as if they were afraid that they were being watched.

They

both looked around them as if they were afraid that they were being watched.

![]() 'This is just the place," I heard the other say.6

'This is just the place," I heard the other say.6

![]()

I Look sharp! — OCTOPOXHO! beperMCb!

2 Ease her! — Ma-llblñ xoa! (,uopœcan KOMaHða)

3 so did the passengers — naccaxMpb1 TOXe (aweon did 3a,ueHqem enaeon shout)

4 "hurrup" l'jurrapl — nonpaxaHue aMepuvxaHCKOMY np0H3H011œH1•no

CJIOBa Europe I 'juarap]

5 as if — KaK 6YAT0

6

| heard the other

say. — yœlbll_nan, KaK apyroii. (oÓbecmHb1ù ![]()

UH(þUHUmU8Hb1Ù oõopom)

26

They sat down and their backs were

turned towards me. I ![]() found myself, against my wish, playing an

unpleasant part of eavesdropper. I

found myself, against my wish, playing an

unpleasant part of eavesdropper. I

"théll, Muller," said the taller of the two, "we've brought it aboard all right. "2

![]() "Yes," agreed the man whom he

had addressed as Muller, "it's safe aboard. "

"Yes," agreed the man whom he

had addressed as Muller, "it's safe aboard. "

![]()

" But we were running a terrible risk.

"Yes, we were, Flannigan," said Muller.![]()

"It would have been horrible if we had missed the ship, "3 said Flannigan.

"Yes, it would," said Muller. "It would have upset our plans. "

For some time the little man smoked his cigar in silence.

![]() 'I have got it here, " he said at

last.

'I have got it here, " he said at

last.

"Let me see it, " said Flannigan.

![]() 'Is no one looking?" asked Muller.

'Is no one looking?" asked Muller.

"No, they are all below."

"We must be very careful, of course," said Muller.

![]() He raised the coat that was hanging

over his left arm, and I saw a dark box which he laid on the deck. One look at

it was enough to make me jump4 to my feet in horror. Ifthey had turned their

heads, they would have seen my pale face looking at them over the pile of

suitcases.

He raised the coat that was hanging

over his left arm, and I saw a dark box which he laid on the deck. One look at

it was enough to make me jump4 to my feet in horror. Ifthey had turned their

heads, they would have seen my pale face looking at them over the pile of

suitcases.

From the first moment of their conversation I had a horrible feeling of danger. Now I was sure that I was right. I looked hard at what lay before me.

It was a little square box of some dark wood. It looked like a pistol-case, only it was much higher. There was a trigger-like arrange-

![]()

I I found myself... playingan unpleasant partofeavesdropperl'i.vzdropal. — q no"Ma-T1 ce6H Ha TOM, "TO 3aHHMaK)Cb [IOACJIYL11MBaHMe,M (MrpaK) HenpHflTHYi0 POJ1b corJ1qnarraq).

2

we've brought it

aboard all right — KaK 6b1 TO HH 6bIJIO, Mb' ero AOCTa![]() Ha napoxoa

Ha napoxoa

3 It would have been horrible if we had missed the shi). — bblJIO 6bl yxacHO, ec,1M 6M Mb' He nonu1H Ha napoxon (cocnaeame]1bHoe HOKnonenue e YCJIOßHOM npeðnoe*thuu mpemeeo muna).

4 was enough to make me jump — 6b1TIO AOCTaT0HH0, wr06b1 3aCTaBHTb

MeHH BCKOHHTb

27

03HaK0MwreAbHa¶

mentl on the lid of the box, and a coil of string was tied to it. Near the trigger was a small square hole in the wood.

![]()

The tall man, Flannigan, as his

companion called him, looked through the hole for several minutes. ![]()

"It seems all right," he said at last.

![]() "l tried not to shake it," said

his companion.

"l tried not to shake it," said

his companion.

"One must be very careful with

such things. Put in what's necessary," said Flannigan.![]()

Then the shorter man took from his pocket a small paper package, opened it, took out some white granules and dropped them through the hole. A funny clicking noise was heard from the box.

Both men smiled. They were pleased.

![]()

" Everything seems all right there, " said

Flannigan.![]()

"Yes, everything is going fine, " answered his companion.

"Look out!2 Here's someone coming.

Take it down to our berth. Nobody should know-3 what our plans are. It will be

very bad for us if anybody finds out about them. And it will be still worse if

anyone pulls the trigger by mistake. He will be terribly shocked, " said

the taller man with a laugh. "It's not badly done, eh?" "Is it

your own design?" asked Muller. ![]() "Yes, it is," was the answer.

"Yes, it is," was the answer.

![]() should take out a patent. "

should take out a patent. "

And the two men laughed again with a cold laugh, as they took up the little box and put it under Muller's coat.

![]() "Let's go down and hide it in our

berth, " said Flannigan. "We shall not need it until tonight, and it

will be safe there. "

"Let's go down and hide it in our

berth, " said Flannigan. "We shall not need it until tonight, and it

will be safe there. "

His companion agreed. They went arm-in-arm4 along the deck. The last words I heard from Flannigan who was telling Muller to carry the box carefully and not to knock it against the sides of the ship.

How long I stayed there, sitting on the coil of rope, I do not remember. I was shaken by the words which I had overheard. Every-

a trigger-like arrangement — I-ITO-TO, noxoxee Ha CHYCKOBOVI KPK)-

YOK

2 Look out! — OCTOPOXHO!

nobody should know — HHKTO He nonxeH 3HaTb (should = must)

4 arm-in-arm — pyKa 06 PYKY

thing seemed to fit in perfectly well. I The two passengers' suitcases were not examined because they had come aboard in a hurry. Their strange manner and secret whispering, the little square box with the trigger, their joke about the shock of the man who would let it off by mistake.. 2 All these facts led me to believe that they were terrorists. They had brought an infernal machine on board and were going to blow up the ship.

I was sure that the white granules which one of them had

dropped into the box formed a fuse-3 for blowing it up.

They said something about "tonight". Was it possible that they were going to carry out their horrible plans on the first evening of our voyage?

What shall I do? Shall I go to the Captain, and tell him about my fears, and put the matter into his hands? The idea was very unpleasant to me. What would be my feelings if it turned out to be a mistake?4 Anything was better than such a mistake. No, I won't go to the Captain. I shall keep an eye5 on the two men and tell nobody about them.

I decided to go down and find them. Suddenly I heard somebody shouting6 in my ear, "Hullo, is that you, Hammond?"

"Oh, " I said, as I turned round, "it's Dick Merton! How are you, old man?"

This was good luck. Dick was just the man I wanted: strong and clever, and full of energy. Ever since I was a small boy in the second form at Harrow7 , Dick had been my adviser and protector. He saw at once that something was wrong with me.

![]()

I Everything seemed to fit in perfectly well. — Bce

KaK 6YAT0 OHeHb xopomo CXOAWIOCb (cyÕbeKmHb1ù

UHØUHUmU8Hb1Ù oóopom). ![]()

2 who would let it off by mistake — KOTOPb1Vt no OUIV16Ke cnycTHT KY-

POK

3 formed a fuse — 3ò. C.TYXMJIH![]()

4

"hat would

be my feelings if it turned out to be a mistake? — I-ITO 6b1 ![]() tiYBCTBOBan, ecr1H 6b1 BCe 3TO

OKa3WIOCb 0111H6KOñ?

tiYBCTBOBan, ecr1H 6b1 BCe 3TO

OKa3WIOCb 0111H6KOñ?

5

to keep an eye

(on) — He BblnyCKaTb H3![]()

6

| heard somebody

shouting — fl ycJ1b1LIJUJ, KaK KIO-TO![]()

(OÕbeKmHblÜ npuqacmHb1ù oõopom) ever since I was a small boy in the second form at Harrow hærou] — co

BToporo KAacca Komenxa B X3ppoy, Koraa H 6b1J1 eue Ma-neHbKHM

29

03HaK0M1-rreAbHa¶ "Hullo!" he said in his friendly way. "What's the matter with you, Hammond? You look as white as a sheet. Feeling sea-

![]() "No, no," I said,

"something quite different! Walk up and down with me,2 Dick, I want to

speak to you. Give me your arm. '

"No, no," I said,

"something quite different! Walk up and down with me,2 Dick, I want to

speak to you. Give me your arm. '

We started walking up and down the deck. But it was some time before I could begin speaking.

![]() 'Have a cigar?" he said, breaking the

silence.

'Have a cigar?" he said, breaking the

silence.

"No, thank you," I said. "Dick, we shall all be dead men tonight.

![]() 'Is that why you don't want a cigar?"

asked Dick calmly. But he was looking hard at me when he spoke. It seemed to me

he thought that I was a little mad.

'Is that why you don't want a cigar?"

asked Dick calmly. But he was looking hard at me when he spoke. It seemed to me

he thought that I was a little mad.

"No," I said, "there is nothing funny here, and I am quite serious. Dick, I've discovered a conspiracy to blow up the ship and everybody on board. "

And then I told him everything I knew.

"There 3 Dick," I said, as I finished, "what do you think of

To my surprise he began laughing.

![]() 'I would have been

frightened if I had heard it from anybody else," he said. "But you,

Hammond, have always liked to discover strange things and make up stories about

them. Do you remember at school how you told us there was a ghost in the

corridor? soon found out it was your own reflection in the mirror. Why, man,

" he continued, "why would anyone want4 to blow up the ship? Why

would these two men want to kill the passengers and themselves too? I am sure you

have mistaken a camera or something like it for an infernal machine. '

'I would have been

frightened if I had heard it from anybody else," he said. "But you,

Hammond, have always liked to discover strange things and make up stories about

them. Do you remember at school how you told us there was a ghost in the

corridor? soon found out it was your own reflection in the mirror. Why, man,

" he continued, "why would anyone want4 to blow up the ship? Why

would these two men want to kill the passengers and themselves too? I am sure you

have mistaken a camera or something like it for an infernal machine. '

![]()

I Feeling seasick? = Are you feeling seasick? — Y Te6q MOPCKaq 60ne3Hb?

2 walk up and down with me — nporynqeMcq (up and down — B3an-Bnepen)

3 there — HY BOT; BOT •raK

4 why would anyone want... — H pauH gero KOMY-TO nompe60Ba.nocb

6bI..

![]() 30

30

"Nothing of the sort, "l I said rather coldly. "l know what I am talking about. As to the box,2 1 have never before seen one like it. They would not have carried it so carefully if it had been only a camera. They were afraid to drop it because there was something dangerous in it.

"Let's go down to the saloon and have a bottle of wine. You can point out these two men if they are there. "

"All right," I answered.

"I'm not going to lose sight ofthem3 all day. Don't stare at them because

I don't want them to think4 that they are being watched.![]()

"All right," said Dick, "I won't."![]()

When we came down to the saloon, a good many passengers were there. But I did not see my men. We passed down the room and looked carefully at every berth. They were not there.

Then we entered the smoking-room. Muller and Flannigan were there. They were both drinking, and a pile of cards lay on the table. They were playing cards as we entered. The conspirators paid no attention to us at all. We sat down and watched them.

There was silence in the smoking-room for some time. Then Muller turned towards me.

"Can you tell me, sir," he said, "when this ship will be heard of again? "5

They were both lookingat me. I tried not to show them how nervous I was.

' I think, 'sir," I answered,

"that it will be heard of when it enters Queenstown Harbour.'![]()

![]() "Ha, ha!"

laughed the angry little man, "l knew you would say that. Don't push me

under the table, Flannigan, I don't like it. I know what I'm doing. You are

wrong, sir," he continued, turning to me, "quite wrong.

"Ha, ha!"

laughed the angry little man, "l knew you would say that. Don't push me

under the table, Flannigan, I don't like it. I know what I'm doing. You are

wrong, sir," he continued, turning to me, "quite wrong.

"The weather is fine," I said, "why should we not be heard of at Queenstown?"

![]()

I Nothing of the sort. — Huqero [10A06Horo.

2

3 to lose sight of them — TepqTb ux M3

4 | don't want them to think — H He

xoqy, HT06b1 OHM![]()

5 when this shi) will be heard of again? — Korna Ha 6epe1Y 6yneT H3BeCTHO o HameM napoxone?

31

031--1aK0MwreAb1--ra¶

"l didn't say that," the man

answered. "l only wanted to say that we should be heard of at some other

place first. ' ![]() "Where then?" asked Dick.

"Where then?" asked Dick.

![]() "That you will

never know, " said Muller. "But before the day is over, some

mysterious event will signal our whereabouts. I Ha, ha, " and he laughed

again.

"That you will

never know, " said Muller. "But before the day is over, some

mysterious event will signal our whereabouts. I Ha, ha, " and he laughed

again.

"Come on deck!" said his

companion angrily. "You have drunk too much and now you are talking too

much. Come away!"![]()

Taking him by the arm, he led him out of the smoking-room

and up to the deck.

"théll, what do you think of it?" I cried, I turned

towards Dick. He was quite calm as usual. ![]()

"Think!" he said. "Why, I think what his companion thinks — that we have been listening2 to the silly talk of a half-drunken man. The fellow can't be responsible for his words. "

"Oh, Dick, Dick," I cried, "how can you be so blind? Don't you see3 that their every word shows that I am right?"

"Nonsense, man!" said Dick. "You are too nervous, that's all. And how do you understand all that nonsense about a mysterious event which will signal our whereabouts?"

"I'll tell you what he meant, Dick," I said. "He meant that some fisherman near the American shore would see a sudden flash

and smoke far out at sea. That's what he meant. '![]()

![]()

'I didn't think you were such a fool, Hammond," said

Dick Merton angrily. "Let's go on deck. You need some fresh air, I think.

'![]()

When it was time to have dinner, I could hardly eat anything. I was sitting at the table, listening to the talk which was going on

around me. I was glad to see that Flannigan was sitting almost in front of me. He drank wine. A few passengers sat between him and his friend Muller. Muller ate little, and seemed nervous and restless.

some mysterious event will signal our whereabouts — HeKoe TMHCTBeHHoe C06b1THe rrpocnrHaJIH3HpyeT o HaweM MeCTOHaXOXueHHH

2

have been

listening —![]()

3 don't you see — 1--1eyxeJIH TH He r10HMMaeLIJb

![]() 32

32

![]() Then our Captain stood up. " Ladies

and gentlemen, " he said, "I hope that you will make yourselves at

homel aboard my ship. A bottle of champagne, steward. Here's t02 our safe

arrival in Europe. I hope our friends in America will hear of us in eight or nine

days. "

Then our Captain stood up. " Ladies

and gentlemen, " he said, "I hope that you will make yourselves at

homel aboard my ship. A bottle of champagne, steward. Here's t02 our safe

arrival in Europe. I hope our friends in America will hear of us in eight or nine

days. "

Flannigan and Muller looked at each other with a wicked

smile.

![]() "May I ask,

Captain, " I said loudly, "what you think of Fenian manifestoes3 and

their terroristic acts?"

"May I ask,

Captain, " I said loudly, "what you think of Fenian manifestoes3 and

their terroristic acts?"

![]() "Oh, Captain,

" said an old lady, "do you think they would really blow up a

ship?"

"Oh, Captain,

" said an old lady, "do you think they would really blow up a

ship?"

![]() "Of course, they would if they

could," said the Captain. "But

"Of course, they would if they

could," said the Captain. "But

![]()

I am quite sure they would never blow up mine. '

![]()

"I hope you've

given orders to make it impossible for them, said an old man at the end of the

table. ![]()

"All goods sent aboard the ship are carefully examined, " said the Captain.

"But a passenger may bring dynamite aboard with him...," I said.

![]()

"I'm sure they would not want to risk their lives in that way, said the Captain.

During this conversation Flannigan didn't show any interest. But he raised now his head andlooked at the Captain.

![]() "Don't you know, " he said,