Публикация является частью публикации:

|

pp.

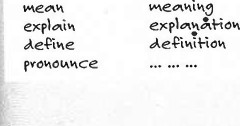

16-25 Ostening how to ...

say hello natural Erglish saying hello listening people introducing themselves

grammar be positive and

pp.

16-25 Ostening how to ...

say hello natural Erglish saying hello listening people introducing themselves

grammar be positive and ![]() negative vocabulary jobs grammar a / an

negative vocabulary jobs grammar a / an

wordbooster

countries and nationalities numbers (1)

reading questions, questions

grammar

questions with be reading an e-mail natural how are you? vocabulary drinks

natural EnglW1 Would you like ![]() . ?

. ?

help with pronunciation and listening

pronunciation sounds listening asking for help natural ErgHsh asking for help

test yourself!

revision and progress check

pp.26-33 reading have you got one?

vocabulary technology natural English thing(s) reading rhe tech shop grammar have got — have

natural English giving opinions (1)

wordbooster

![]() personal things possessive •s

adjectives (1)

personal things possessive •s

adjectives (1)

![]() listening how to .

listening how to . ![]() ask for things

ask for things ![]() Can I .. . ?

Can I .. . ?

grammar this, that, these, those

listening classroom talk natural saying you aren't sure writing note writing

help with pronunciation ![]() and listening

and listening ![]()

pronunciation word stress listening information words

test yourself!

revision and progress check

|

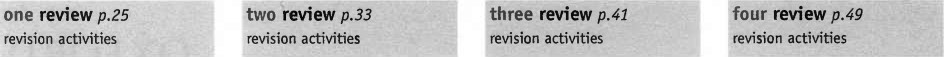

in unit one . |

|

|

in unit two . |

|

|

in unit three . |

|

in unit four . |

istening you and me

vocabulary noun groups 'ocabulary daily routines grammar present simple rammar present simple with natural a lot (of) frequency adverbs listening transport survey ading Who reads most? natural English get Where do people read?

grammar wh- questions òatural about an hour week wordbooster telling the

time „wordbooster natural English asking the time days, months, and seasons

leisure activities time phrases with prepositions reading how to ... ![]() listening

how to

listening

how to

|

talk about likes and |

talk about your family |

|

dislikes |

vocabulary families |

|

natural English likes and dislikes |

natural Engfish asking about |

|

grammar present simple with |

family |

|

he / she |

grammar my, your, etc. |

|

reading Workers of the World |

listening people talking about families natural English (do something) together writing about families |

extended speaking![]() help with pronunciation how active

are you? and listening

help with pronunciation how active

are you? and listening

![]() collect ideas pronunciation sounds

/ö/ and listen do an interview listening weak forms write a paragraph

natural saying thank you

collect ideas pronunciation sounds

/ö/ and listen do an interview listening weak forms write a paragraph

natural saying thank you

test yourself! test yourself!

revision and progress check revision and progress check

one two wordlist p.131 three p.132 four wordlist p.133

2

units one to ei ht

|

in unit five |

|

|

|

in unit six . |

|

|

in unit seven . |

|

in unit ei |

ht . |

![]() pp.50-57

ading breakfast time

pp.50-57

ading breakfast time ![]()

butary breakfast food ural EngW1 What do you have for... ?![]()

mmar countable and ![]() uncountable nouns mar some / any

uncountable nouns mar some / any ![]()

'reading Round the world at

8.00 a.m.

•ng write about breakfast time

'ordbooster

NturalEnghsh What kind of ![]() . ?

. ?

'djectives (2)

Qistening how to ![]() order food

order food

grammar can / can't 4 verb listening ordering food natural English ordering food natural Enghsh asking for more

ended speaking

ended speaking ![]() hays on the menu?

hays on the menu?

Ilect ideas

test yourself!

revision and progress check

|

•sion |

pp.58-65 reading a day out

vocabulary tourist places ![]() past simple was / were reading I'm a guide

past simple was / were reading I'm a guide ![]() natural English both

natural English both

![]()

wordbooster ![]()

![]() past time phrases

past time phrases ![]() verb + noun collocation listening how

to

verb + noun collocation listening how

to ![]() talk about [ast weekend

talk about [ast weekend ![]() natural Engfish How was ... ? grammar past simple: regular and irregular

verbs listening talking about the weekend natural English showing you are

listening writing weblogs

natural Engfish How was ... ? grammar past simple: regular and irregular

verbs listening talking about the weekend natural English showing you are

listening writing weblogs

help with pronunciation ![]() and listening

and listening ![]()

pronunciation sounds /o:/, /3:/, and ID/ listening prediction (1)

test yourself!

revision and progress check

![]() pp.66-73

heading biographies

pp.66-73

heading biographies

![]() vocabulary life story

vocabulary life story ![]() grammar past simple: negatives

grammar past simple: negatives ![]() reading Before she was famous..

reading Before she was famous.. ![]() natural •sh link words:

natural •sh link words: ![]() then

/ a r that grammar past

simple: questions

then

/ a r that grammar past

simple: questions

![]()

wordbooster

appearance ![]() natural English quite

and very character

natural English quite

and very character

listening how to ![]() talk about people you know

talk about people you know

grammar object pronouns natural English What's he / she like ? listening people talking about their teachers natural English When did you last ... ?

extended speaking ![]() people from your past

people from your past ![]()

collect

ideas prepare an interview ![]() interview tell a story writing

interview tell a story writing

test yourself!

revision and progress check

pp. 74-81 reading I got lost! ![]()

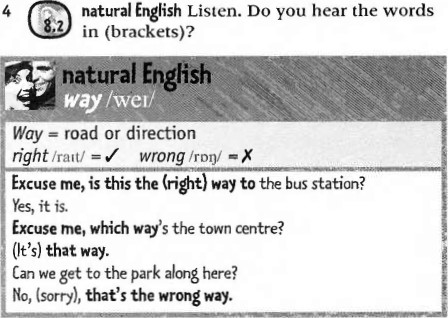

vocabulary getting around ![]() natural EngHsh way

reading Excuse me, where's Paris? Excuse

me, where's Bath? grammar•how much / many

natural EngHsh way

reading Excuse me, where's Paris? Excuse

me, where's Bath? grammar•how much / many ![]()

wordbooster ![]()

prepositions of place come and go; bring and take

listening how to ... get round a building

grammar there is / are listening asking for directions natural English asking for directions natural English well vocabulary directions

help with pronunciation and listening

pronunciation sounds /J/, /tJ/, and Ids/ listening prediction (2) natural English asking people to speak slowly / speak up

test yourself!

revision and progress check

five six wordlist p. 135 seven p.136 eight wordlist p.137

|

in unit nine |

![]()

reading backpacking ![]() reading babies

reading babies

|

vocabulary hotels |

natural English giving opinions |

|

natural English I (don't) think so |

grammar something, anything, |

|

listening booking hotel rooms |

nothing, etc. |

|

natural English Would you |

listening offering help |

|

prefer ? |

natural English offering help writing explaining problems and offering help |

|

extended speaking |

help with pronunciation |

|

my kind of hotel |

and listening |

![]()

![]() grammar have to / don't have

vocabulary action verbs to/ dol have to ?

grammar have to / don't have

vocabulary action verbs to/ dol have to ? ![]() natural English talking about can /

can't (permission) ages reading Youth hostels: reading Watch your baby grow! frequently

asked questions grammar

can / can't (ability) natural English normally natural English quite / very

well writing an e-mail wordbooster wordbooster parts of the body numbers (2)

common phrases money listening how to listening how tooffer help book a room

natural English talking about can /

can't (permission) ages reading Youth hostels: reading Watch your baby grow! frequently

asked questions grammar

can / can't (ability) natural English normally natural English quite / very

well writing an e-mail wordbooster wordbooster parts of the body numbers (2)

common phrases money listening how to listening how tooffer help book a room

|

|

|

nine p.89

revision

nine ten wordlist p.139

grammar comparative adjectives -reading Quicker than a car?

natural How long does it take? Ntural English agreeing and disagreeing wordbooster

shops and products natural get buy) adjectives (3)

listening how to recommend

natural English recommending: should + verb listening people talking about

holiday places grammar superlative adjectives writing correcting a text

![]()

![]() extended speaking town survey collect

ideas

extended speaking town survey collect

ideas

prepare a survey listen do the survey compare answers

test yourself!

revision and progress check

eleven p.140

|

in unit ten . |

|

in unit eleven . |

|

in unit twelve . |

natural English How about you? reading The luncheon of the boating party grammar present continuous

wordbooster clothes telephoning

listening how to . use the phone natural English mostly grammar present simple vs continuous listening phoning friends natural English phoning a friend natural English telephone introductions writing a conversation and a message

help with pronunciation and listening

pronunciation consonant groups listening being an active listener natural English showing you (don't) understand

test yourself!

|

activities |

revision and progress check iwelve

revision and progress check iwelve

revision twelve wordlist p.141

nine to fourteen

nine to fourteen

|

in unit thirteen |

|

in unit fourteen . |

teacher pp.114-121 pp.122-129 development

teacher pp.114-121 pp.122-129 development

a new life![]() reading that's incredible!

reading that's incredible! ![]() chapters

chapters

Get a new life ![]() natural How many

times . ? how to mmar be going to + verb;grammar present perfect

natural How many

times . ? how to mmar be going to + verb;grammar present perfect ![]() use the board

use the board

![]() Erghsh + verb What are you

Erghsh + verb What are you ![]() reading breakersKing of the record p.

146

reading breakersKing of the record p.

146 ![]() natural English tonight? -natural reacting to website

ng filling in forms surprising information how to

natural English tonight? -natural reacting to website

ng filling in forms surprising information how to![]() www.oup.com/elt/teacher/

grammar present perfect

and develop learner

www.oup.com/elt/teacher/

grammar present perfect

and develop learner![]() naturalengtish rdbooster

naturalengtish rdbooster ![]() past simple independence Extra class activities

and

past simple independence Extra class activities

and

![]() p.153 resources

and links to the rb +

preposition

p.153 resources

and links to the rb +

preposition ![]() student's site. English Do you ever P wordbooster how

to .

student's site. English Do you ever P wordbooster how

to .

![]()

•nds Of film opposites also available

|

natural English test booklet |

|

communicate with feelings low-level learners

'listening how to ![]() invite someone listening how to p.160

invite someone listening how to p.160

![]() igtural EngHsh inviting and say what you feel how to

igtural EngHsh inviting and say what you feel how to ![]() responding vocabulary fixed phrases

select, organize, and listening people arranging to go natural English special

greetings present vocabulary at to the cinema listening someone giving a lower

levels

responding vocabulary fixed phrases

select, organize, and listening people arranging to go natural English special

greetings present vocabulary at to the cinema listening someone giving a lower

levels

|

natural English have a + adj + noun |

how to . |

test booklet |

|

|

help low-level learners |

Unit-by-unit tests for |

|

|

with pronunciation |

grammar, vocabulary, and |

|

|

p.174 |

natural English plus seven skills tests. Common examstyle questions in 'exam focus' sections throughout. |

|

reading writing skills |

|

|

|

|

|

Complements the natural |

|

test yourself! |

test yourself! |

English reading and writing syllabuses. |

|

revision and progress check |

revision and progress check |

— an extra reading lesson |

utended speaking help

with pronunciation language reference key

utended speaking help

with pronunciation language reference key

(s go out! and listening pp. 181-183

Ilect ideas listening to a song 'invent information pronunciation linking

bractice le play reading & writing skills resource book

for every unit of the

![]() 'teen review

p.121fourteen review p.129 student's

book

'teen review

p.121fourteen review p.129 student's

book

•sion activitiesrevision activities — material related to the

student's book by topic

— develops real life reading

Thirteen wordlist p.142 fourteen wordlist p.143 and writing skills useful

for work or study

— advice on text types and skills

Before we established the language syllabus for the elementary level of natural EngHsh, we wanted to be sure that what we set out to teach learners corresponded to what they actually needed to learn at this stage in their language development. So, instead of starting with a prescribed syllabus, we began by planning a series of communicative activities with certain criteria:

— they would have to be engaging,

purposeful. and achievable — they would need to stretch the limited resources

of elementary learners ![]()

— they had to include different topics, and past and future time frames as well as the present

— they should cover a range of activity types (e.g. giving and exchanging information; service encounter role plays; sharing experiences; telling simple stories, etc.)

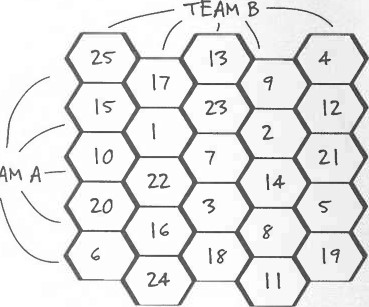

We then wrote the activities. Initially, we produced more than we needed, and after trialling, we eliminated those which did not work as well as we had hoped or overlapped with others which were richer in language or more successful. Those that remained became the activities which you will find in the extended speaking activities and it's your turn! sections in a much refined and reworked form, thanks to the learner data and feedback from teachers. Here are two examples from the

We

asked teachers to use the material with their elementary classes, and record

small groups doing the activities. We also piloted them ourselves with small

groups. In all, we recorded over one hundred learners from at least a dozen

different countries. In our earlier research (at intermediate and

upperintermediate levels) we had done a limited amount of piloting of native

speakers doing the relevant activities, but at this level we didn't think it

would be of great benefit. However, following on from our experience at the

higher levels, we did pilot the activities with learners above the target

level, so we recorded pre-intermediate level students as well.

After transcribing the recordings, we had a considerable amount of data al elementary level, but also data at the level just above elementary. As with the previous levels, the comparisons were fascinating, and knowing what could be achieved just above the target level was very informative in helping us to identify the most useful, relevant and achievable target language for elementary learners. At that point we were able to start writing the student's book.

To summarize. the development of the course involved the following stages:

I devise the extended speaking activities / role plays for trialling

2 trial and record elementary and pre-intermediate learners

3 transcribe and analyse the data

4 select appropriate language for the syllabus

5 write the learning materials

what is natural English?

Throughout the course we have tried to identify language relevant to the needs of learners at each respective level. For the most part, that has meant the inclusion of high-frequency language used naturally by native speakers and proficient users of the language: if a word or phrase is used frequently, it is likely to be useful in a range of everyday communication.

However, not all language used naturally by native speakers is necessarily suitable for many foreign learners, and that includes some high-frequency language. Our own classroom experience has taught us that many learners find it difficult to incorporate highly idiomatic language into their own interlanguage, and a word or phrase which sounds very natural when used by a native speaker can have the opposite effect when used by an L2 learner — it sounds very unnatural. We have, therefore, tried 10 focus on language which is used naturally by native speakers or proficient speakers of the language, also sounds natural when used by L2 learners. So, at this elementary level for example, we want learners to use high-frequency and relatively informal ways of thanking people such as thanks and thanks a lot; but we have not introduced the more colloquial phrases such as cheers or ta.

How does anyone decide exactly what language will fulfil these criteria? It is, of course, highly subjective. As yet, there isn't a readily available core lexicon of phrases and collocations to teach elementary learners on the basis of frequency, let alone taking into account the question of which phrases might be most 'suitable' for learners at this level. Our strategy has been to use our own classroom knowledge and experience to interpret our data of elementary and pre-intermediate level

language use, in conjunction with information from the Longman Grammar Of Spoken and Written English, a range Of ELT dictionaries and data from the British National Corpus and The Oxford Corpus Collection. In this way, we arrived at an appropriate language syllabus for elementary learners.

what else did we learn from the data?

These are some of the general findings to emerge from our data, which influenced the way we then produced the material.

![]()

level of confidence

Most learners at this level (but by no means all) lack the confidence to experiment with language. This showed up in the trialling with some learners treating communication activities as language drills. Of course, learners need controlled practice to help them to produce language accurately and more automatically, but they also need opportunities to use language freely — to develop fluency by thinking more about they are saying than they are saying it. For this reason, we felt that freer speaking activities were still relevant to this level, and we have included them throughout the book in it's your turn! at the end of every lesson, and extended speaking activities at the end of every unit (from unit three onwards).

When learners engage in genuine communication they will inevitably make mistakes. Throughout the notes in the teacher's book, we have tried to anticipate errors and minimize these, but at the same time we believe that mistakes are part of the learning process and should be viewed constructively in the classroom, i.e. what can we learn from them for future productive use?

length of turns

Throughout the data we saw evidence of very short turns (even shorter than at the pre-intermediate level). This is to be expected, but we have tried to extend utterances by building into activities a lot of planning and rehearsal time. In addition, we feel that structuring speaking activities is essential to ensure that learners have plenty to talk about. Listening models or teacher models which show students how they can develop topics are also instrumental in encouraging more output and longer turns.

listening and pronunciation

At this level, more than any other, we found that learners had difficulty understanding one another (particularly in multilingual classes). Apart from cultural misunderstandings, problems seemed to arise from two sources: poor comprehension skills on the part Of the listener, and / or lack Of intelligibility through poor pronunication on the speaker's part. We have addressed this issue throughout the elementary material, but with an extra focus (at the end of alternate units) in a new section called help with pronunciation and listening. See

grammar

Many elementary learners have 'studied' grammar such as the present and past simple, but it was clear that productive use is still exceedingly difficult. There was a lot of simplification throughout the data, and many learners at this level are only truly comfortable when operating in the present simple, and even then inaccurately. We also found that learners were uniformly poor at asking questions, and their use Of modal verbs was almost non-existent.

In response you will find considerable attention is paid to all of these areas.

vocabulary

The most obvious shortcoming was the lack of familiarity with high-frequency phrases in a number of everyday situations. For example, we found that learners weren't able to ask about people's weekend (How was your weekend?), order food in a restaurant (Could I have some more... / another.... please?), reassure people (don't worry), etc. The language in the natural English boxes is the most obvious way we have tackled this shortcoming, but you will find a number Of common lexical chunks throughout the wordboosters and other vocabulary development exercises.

how to use key features of natural English

• natural EngfiTh boxes

• wordbooster

• staged listening

• help with pronunciation and listening

• test yourself!

• language reference and practice exercises

• reviews

• workbook

• teacher's book

• skills resource book • test booklet natural English boxes

Most of the natural English boxes consist of natural English phrases. They normally occur four times in each unit, with one or two boxes in each main section, and often one in the wordbooster.

what do the natural English boxes contain?

These boxes focus on important aspects of everyday language, some of which fall outside the traditional grammatical / lexical syllabus. They include:

— familiar functional exponents, e.g. suggesting and responding

(We could go to the cinema. Yeah, that's a good idea.)

— communication strategies, e.g. asking for help (Sorry, can you repeat

that, please?) ![]() high-frequency words in spoken

English, e.g. get, quite / very, mostly

high-frequency words in spoken

English, e.g. get, quite / very, mostly

— common features Of spoken English, e.g. vague language

(thing), qualifying (a bit)

— lexical chunks, e.g. Have a nice time, Anything else? What's the matter?

The language here is presented in chunks, with each box containing a limited number Of words Or phrases to avoid memory overload. The words / phrases are practised On the spot, and then learners have the opportunity to use them later in freer activities, e.g. in it's your turn! or the extended speaking activity.

These boxes have been positioned at a point within each cycle where they are going to be of immediate value, and most of the phrases are recorded to provide a pronunciation model. There is an instruction before each natural English box providing learners with a task to highlight the forms and / or focus on meaning, e.g. Listen and complete the questions or Match the questions and answers (in the box). Beneath each box there is a controlled practice exercise to focus on pronunciation and consolidate meaning. and in many cases this is followed by a personalized practice activity. In the classroom, you could vary the presentation of the language in the following ways:

— If the target phrases have been recorded, you could ask learners to listen to them first. They could do this with books shut and treat it as a dictation, then compare their answers with the student's book; or they could listen and follow in the student's book at the same time, and then repeat from the recording or the model that you give them yourself.

— You can read the phrases aloud for learners to repeat; alternatively, you can ask individual learners to read them out as a way of presenting them.

— You can ask learners to read the box silently, then answer any queries they have, before you get them to say the phrases.

— You could write the phrases on the board or OHP for everyone to focus on. Then ask learners about any problems they have with meaning and form of the examples before practice.

— You could sometimes elicit the phrases before learners read them. For instance, ask them how they could ask for directions. or what they would say when offering food or drink. Write their suggestions on the board, and then let learners compare with the natural English box. In some cases learners will know some important phrases, but they may not be very accurate or know the most natural way to express these concepts.

— Once learners have practised the phrases, you could ask them to shut their student's book and write down the phrases they remember.

![]() If you have a weaker class, you might

decide to focus on only one or two Of the phrases for productive

practice; for a stronger group, you may want to add one or two phrases Of your own.

If you have a weaker class, you might

decide to focus on only one or two Of the phrases for productive

practice; for a stronger group, you may want to add one or two phrases Of your own.

— For revision, you could tell learners they are going to be tested on the natural English boxes of the last two units you have done; they should revise them for homework. The next day, you can test them in a number of ways:

— give them an error-spotting test ![]() fill gaps in phrases or give stimuli

which learners respond to — ask them to write two-line dialogues

in pairs

fill gaps in phrases or give stimuli

which learners respond to — ask them to write two-line dialogues

in pairs

![]() The workbook provides you with a

number of consolidation and further practice exercises of natural English (and,

of course, other language presented in the student's book — see below for more

details).

The workbook provides you with a

number of consolidation and further practice exercises of natural English (and,

of course, other language presented in the student's book — see below for more

details).

— As the phrases are clearly very useful, you may want to put some of them on display in your classroom. You could also get learners to Start a natural and vocabulary notebook and record the phrases under headings as they learn them. You should decide together whether natural (rather than literal) translations would be a useful option for self-study.

![]()

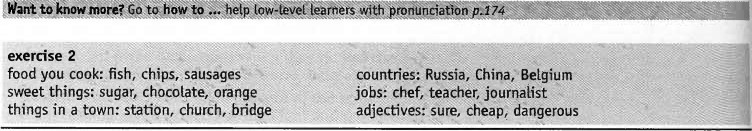

wordbooster

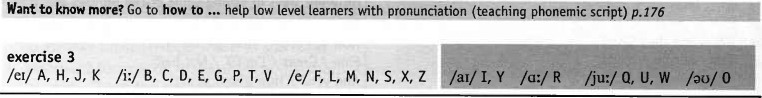

Wordbooster is a section in each unit devoted to vocabulary development. It is almost always divided into two parts, each one focussing on a different lexical area: at least one is topicbased, the other may also be topic-based or focus on collocation, e.g. verb + preposition, or verb + noun.

why wordbooster?

Throughout the other sections in each unit, you will find vocabulary input which is practised within the section. The wordbooster sections have two main aims:

— they present much of the key vocabulary that learners will need in the how to... lesson. and I or the extended speaking activity at the end of the unit.

— they also cover topic areas and linguistic areas which sometimes go beyond the immediate requirements of the fourteen units and so help to provide a more comprehensive vocabulary syllabus. The wordbooster section is designed to have a different feel from the other more interactive sections in the course, and it provides a change of pace and activity type.

how to use wordbooster

Each wordbooster will take approximately 30-45 minutes to complete, and it can be used flexibly.

![]() You don't need to do the whole wordbooster in one session. As it

is divided into two sections, you can do one part in one lesson, and the other

part in a later lesson. In other words, you can use this section to fit in with your own teaching

timetable. For instance, if you have 15-20 minutes at the end of

a lesson, you can do one

of these sections.

You don't need to do the whole wordbooster in one session. As it

is divided into two sections, you can do one part in one lesson, and the other

part in a later lesson. In other words, you can use this section to fit in with your own teaching

timetable. For instance, if you have 15-20 minutes at the end of

a lesson, you can do one

of these sections.

— You can do some of it in class, and some of it can be done for homework.

— Encourage learners to record the language learnt in these sections in their natural Engfish and vocabulary notebooks.

In the natural English course. listening is a very important component in all four levels. Much of the recorded material is improvised, unscripted and delivered at natural speed, and where practical, this approach has also been adopted at elementary level. At the same time, there is a balance of scripted material as learners at this level adjust to the demands of natural, spoken English.

As with other levels of the course, we have included a threephase listening section in each unit:

![]() tune in: a short extract from the

beginning of the main listening. This gives learners the

opportunity to tune in to the voices of the speakers and the content of the

listening passage with a

simple accompanying task.

tune in: a short extract from the

beginning of the main listening. This gives learners the

opportunity to tune in to the voices of the speakers and the content of the

listening passage with a

simple accompanying task.

— listen carefully: the main listening passage. Students hear the introduction (tune in) again, and then the rest of the passage, with a more detailed task.

![]() listening challenge: a further

listening passage (cither a continuation of the main listening, or a parallel

listening passage) in which the listening tasks are less guided and more open.

listening challenge: a further

listening passage (cither a continuation of the main listening, or a parallel

listening passage) in which the listening tasks are less guided and more open.

how to use staged listening

— As the listening material has been staged in order to ease learners gently into the main listening and build their confidence, it is important to use tune in and listen carefully as in the student's book. However, listening challenge can sometimes be used at a later stage if it is not a continuation of listen carefully, e.g. in unit 7 (T7.8).

![]() At a certain point in the listening

cycle, the student's book indicates the best point at which to go to the

tapescript (p.146 — p. 156). Following the tape-script after one

or two attempts at

listening is a valuable way for learners to decode the

parts they haven't understood; it is not only very useful, but also a popular activity. You

could encourage learners to make a note of new vocabulary from tapescripts,

especially as the recordings are a source of natural, spoken

English.

At a certain point in the listening

cycle, the student's book indicates the best point at which to go to the

tapescript (p.146 — p. 156). Following the tape-script after one

or two attempts at

listening is a valuable way for learners to decode the

parts they haven't understood; it is not only very useful, but also a popular activity. You

could encourage learners to make a note of new vocabulary from tapescripts,

especially as the recordings are a source of natural, spoken

English.

help with pronunciation and listening

This is a new section for elementary level.

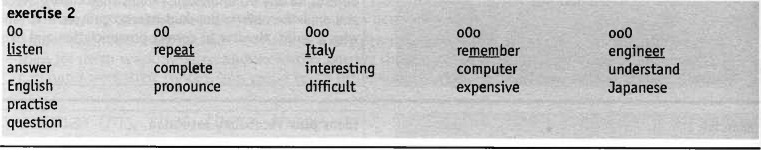

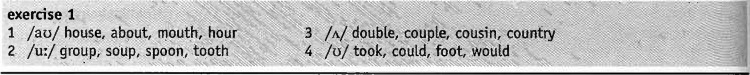

Pronunciation sections aim to help learners improve their ability to produce mainly sounds and word stress more accurately. In some cases, the sounds may be isolated for teaching purposes, but in the exercises, the sounds are contextualized in sentences. As learners work through the material, they build up a knowledge of phonemic symbols, which are gradually incorporated within the rest of the material in the phonemic transcriptions of new vocabulary items. The activities are all short and self-contained.

![]()

Each listening section aims to develop a particular listening subskill:

— asking for help if you don't understand

- listening for key words

— recognising weak forms

- predicting content

- understanding features of connected speech - being an active listener

how to use help with pronunciation and listening

Each help with pronunciation and listening section will take approximately 30-45 minutes to complete.

- You don't need to do all of it in one session. As it is divided into two sections, you can do one part in one lesson, and the other part in a later lesson. In other words (as with wordbooster), you can use this section to fit in with your own teaching timetable. For instance, if you have 15-20 minutes at the end of a lesson, you can do one of these sections.

— Both sections recycle previously taught language, so it is advisable to use them where they are positioned in the course, although in most cases, it is possible to reverse the order of the two sections.

— As the students build up a knowledge of phonemic symbols, try to incorporate them in your own teaching, e.g use them to highlight difficult sounds in new vocabulary items. You can refer learners regularly to the phonemic chart at the back of the student's book p.158 for further consolidation.

— At the beginnning of each listening section, there is a speech bubble which highlights the subskill learners are going to practise. These subskills have been described in very simple terms so that learners can understand them, and it is important to make them aware of the specific aim of each section.

![]()

test yourself!

Test yourself! is an end-of-unit test or revision activity enabling learners

to assess their progress, and consider how they performed in the extended speaking activity. It is a

short, easily administered test covering lexis, natural English

phrases, and grammar from the unit in a standardized format: ![]() producing

items within categories

producing

items within categories

— gap-fill

— correcting errors how to use test yourself!

You can use it either before the extended speaking activity, for revision purposes, or as an end-of-unit lest. You may want to give learners time to prepare for it, e.g. read through the unit for homework, or make it a more casual and informal revision activity. Make it clear to learners that their answers in the test should only include new language from the unit.

The test can be used in different ways: — A formal test. Ask learners to complete it individually, and then collect in their answers to mark.

— An informal test. Ask learners to complete it individually, then go through the answers with the whole class.

— A more interactive test. Ask learners to complete it in pairs. Go through the answers with the class, or ask a pair to mark the answers of another pair.

— You could get learners to complete the test individually or in pairs, then they can check their answers by looking back through the unit. Asking learners to search for answers in this way may not give you as much feedback on their progress, but it may be more memorable for them as learners.

— You could give the test for homework. Learners can then use the unit material as they wish.

Refer learners back to the checklist of the language input at the beginning of the unit. They can then tick which areas they feel more confident in. This is an important way for you to discover which areas they feel they need to revise. You may still have language reference and practice exercises, workbook exercises, and review sections which you can use for this revision.

language reference and practice exercises

The language reference section contains more detailed explanations

of the key grammar and lexical grammar in the units, plus a large bank of practice exercises, which

have been included for two main reasons: ![]()

— they make the language reference much more engaging and interactive.

— they provide practice and consolidation which teachers and learners can use flexibly: within the lesson when the grammar is being taught, in a later lesson for revision purposes, or for self-study.

Most of the exercises are objective with a right-or-wrong answer, which makes them easy for you to administer.

how to use the language reference and practice exercises

— Use them when the need arises. If you always tell learners to read the language reference and do all the practice exercises within the lesson. you may have problems with pace and variety. Rather, use them at your discretion. If, for instance, you find that the learners need a little more practice than is provided in a grammar section, select the appropriate exercise (e.g. unit one, be positive and negative: do exercises 1.1 and 1.2 in practice). Areas of grammar are not equally easy or difficult for all nationalities. The practice exercises provide additional practice on all areas; you can select the ones which are most relevant to your learners.

![]() The practice exercises are ideal for self-study. Learners can read the

explanations on the left, then cover them while they do the exercises on the

right. Finally, they can look again at the explanations if necessary. You can give them the answers to

these practice exercises which are at the end of this teachers book

pps.181-183.

The practice exercises are ideal for self-study. Learners can read the

explanations on the left, then cover them while they do the exercises on the

right. Finally, they can look again at the explanations if necessary. You can give them the answers to

these practice exercises which are at the end of this teachers book

pps.181-183.

— If learners write the answers in pencil or in a notebook, they will be able to re-use the exercises for revision. Some learners also benefit from writing their own language examples under the ones given in the language reference. They can also annotate. translate. etc.

reviews

Review sections occur at the end of every unit in the studenes book. These activities revise the main grammar, vocabulary and natural English. Some of them can be done individually, but there is an interactive element in most, which is designed to help learners to consolidate their understanding and ability to use the language productively. They have not been constructed as objective tests.

how to use the review

You have several options:

— you could use the review sections as they occur, i.e. review each unit when you have completed it.

— you could use individual activities within a review section at different times, e.g. use a review grammar activity after you have completed the grammar section in the unit, but possibly save the natural English review activity for a later lesson.

— you could do some activities in class and set others for homework.

In other words, the review sections have been designed so that you can use them flexibly to fit in with your teaching programme.

workbook

The workbook recycles and consolidates vocabulary, grammar, and natural Enghsh from the student's book. It also provides language extension sections called expand your grammar and expand your vocabulary for stronger or more confident learners. These present and practise new material that learners have not met in the student's book. Another important feature of the workbook is the say it! sections, which encourage learners to rehearse language through promoted oral responses. There are two other regular features: think back! (revision prompts) and write it! (prompts for writing tasks). You can use the workbook for extra practice in class or set exercises for learners to do out of class time. The with key version allows learners to use the workbook autonomously.

teacher's book

This teacher's book is the product of our own teaching and teacher training experience combined with extensive research carried out by Oxford University Press into how teacher's books are used.

The teaching notes are presented as flexible lesson plans, which are easy to dip into and use at a glance. We talk you through each lesson, offering classroom management tips (troubleshooting), anticipating problems (language point), giving additional cultural information (culture note), and suggesting alternative ways of using or extending the material (ideas plus). In addition, each lesson plan provides you with the exercise keys, a summary of the lesson contents, and the estimated length of the lesson.

At the end of each teacher's book, there's a photocopiable wordlist of natural Enghsh phrases and vocabulary items for each unit of the student's book. This is a useful reference for you, and a clear, concise record for the learners, which they can annotate with explanations, translation, pronunciation, etc. and use for their own revision.

teacher development chapters

You'll find the teacher development chapters after the lesson plans, starting on p.146. These practical chapters encourage reflection on teaching principles and techniques. At elementary level the areas covered are:

—

how to ![]() use the board p.146

use the board p.146

—

how to ![]() develop learner independence p.153

develop learner independence p.153

—

how to ![]() communicate with low-level learners p.160

communicate with low-level learners p.160

— how to ![]() select,

organize, and present vocabulary

select,

organize, and present vocabulary

at lower levels p.167

— how to help low-level learners with pronunciation p.] 74

The chapters are regularly cross-referenced from the lesson plans, but you can read them at any time and in any order.

Each chapter contains the following features:

— think! tasks for the reader with accompanying answer keys

(see p.146)

— try it out boxes offering practical classroom ideas

related to the topic of the chapter (p.151) ![]() natural EngHsh student's book extracts to illustrate

specific points (see p.165)

natural EngHsh student's book extracts to illustrate

specific points (see p.165) ![]() follow-up sections at the end of each chapter

providing a short bibliography for further reading on the

topic (see p.166).

follow-up sections at the end of each chapter

providing a short bibliography for further reading on the

topic (see p.166).

This book also contains a photocopiable key to the student's book language reference section (pps.181—183).

For reference, a pronunciation chart on p.14 shows the pronunciation syllabus across the elementary student's book.

![]() in the reading and writing skills resource book?

in the reading and writing skills resource book?

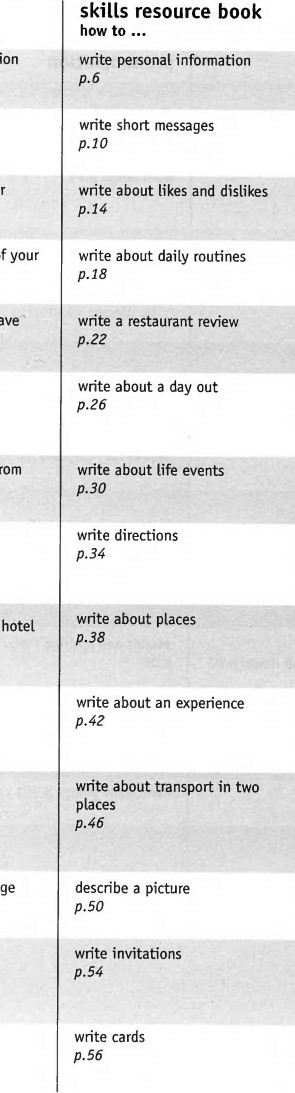

The 64-page photocopiable resource book contains 14 reading lessons and 14 writing lessons, i.e. one reading lesson and one writing lesson for each unit of the elementary student's book, on a similar theme. Each lesson lasts between 30 and 60 minutes and is accompanied by easy-to-use teacher's notes.

The reading lessons are based around a range of authentic texts from website and newspaper articles to e-mails, recipes. and letters. The aim is to expose students to a number of different and accessible text types whilst giving practice in •real world' reading skills. It includes the basic reading skills on a regular basis, but slightly more challenging ones are also introduced in the later units. Here are some of the skills you will find (the headings on the student's pages have been simplified for the level): - predicting

— activating background knowledge

— reading for gist

- understanding the main points

- reading for specific information

- reading for details

— responding to the text

The writing lessons are based around model texts which students then analyse for relevant features of language and style. Students are helped with ideas and planning, and each lesson culminates in a writing task that can be done in class time or set for homework. Regular spell check boxes focus on key points as they arise in the model texts. The writing lessons are divided into the following areas:

-how to

![]() write personal information

write personal information

—how to ![]() write short messages —how to

write short messages —how to![]() write

about likes and dislikes

write

about likes and dislikes

—how to![]() write

about daily routines

write

about daily routines

—how to![]() write

a restaurant review

write

a restaurant review

—how to![]() write about a day out

write about a day out

—how to ![]() write

about life events

write

about life events

-how to ![]() write

directions

write

directions

—how to .![]() . write about places

. write about places

- how to ![]() write

about an experience

write

about an experience

-how to ![]() write

about transport in two places

write

about transport in two places

-how to ![]() describe

a picture

describe

a picture

—how to

![]() write invitations

write invitations

-how to ![]() write cards

write cards

In addition, students are encouraged to assess their own progress in reading and writing by using the self-assessment chart at the back of the book. There are also vocabulary diaries for students to keep a record of new words they have encountered in the reading and writing lessons.

The interleaved teachers notes are set out in a simple grid with answer keys and guidance notes clearly visible at a glance. There is advice on particular text types and how to help students develop their reading and writing skills. The ideas plus boxes give suggestions on how to exploit the material further.

how to use the skills resource book

The reading and writing skills resource book is designed to be used in class to supplement the natural English elementary studenrs book. It can be used to build on and extend the reading and writing skills already covered in the student's book, or as a stand-alone reading and writing course. It is also intended that the elementary level will prepare students for the kinds of reading and writing skills that they may meet in the pre-intermediate, intermediate, and upper-intermediate skills resource books.

The elementary test booklet provides photocopiable unit-byunit tests for the grammar, vocabulary, and natural Enghsh syllabus, and skills tests for every two units at the back of the book. The skills tests cover reading, writing, speaking, and listening. The listening tests re-use the student's book material but exploit it using different tasks. 'Live' dictations are also provided if you wish to use listening material which will be entirely new to the students.

The test booklet also contains exam-style question types in regular exam focus sections. These appear at the end Of each unit test and throughout the skills tests. The aim is to give students practice and confidence in tackling common exam-style questions. An answer key is provided at the back.

writing in natural English

writing in natural English

student's book

•unit onepersonal information

unit two write a note

p.20

unit three write about your partner

unit four write about a member of your

•unit fiveabout what you have for breakfast

•unit fiveabout what you have for breakfast

unit six write a weblog

write about somebody

from your past

write about somebody

from your past

unit eight write directions

![]() it nine write an e-mail about

a hotel

it nine write an e-mail about

a hotel

unit ten write about a problem

![]() eleven write

about a place

eleven write

about a place

unit twelve write a telephone message

p.100

![]() nit thirteen fill in a form

nit thirteen fill in a form

unit fourteencards

skills resource book

write personal information

messages

write about likes and dislikes

write about daily routines

write a restaurant review

write about a day out

life events

write directions

write about an experience

write about transport in two

write invitations

elementary

skills / tasks

read a letter, understand capital

letters and full stops, ![]() complete a form, write about you, spell check writing task: a letter to a

host family

complete a form, write about you, spell check writing task: a letter to a

host family

think about the topic, understand requests, organize sentences, spell check, make requests writing task: a message to a flatmate

![]()

think about you, read an e-mail, understand and and but, use commas, write about you, spell check writing task: an e-mail to a classmate

![]()

think about the topic, spell check, write about daily routines, order sentences, order ideas, use your ideas writing task: an article about another person

![]()

think about the topic, read a review, understand

adjectives, understand it, spell check, use because ![]() writing task: a

restaurant review

writing task: a

restaurant review

![]()

![]() think about

the topic, read a narrative, understand because and so, spelt check, use

punctuation writing task: an e-mail or letter to a friend about a day (or

night) out think about the topic, spell éheck, understand an

think about

the topic, read a narrative, understand because and so, spelt check, use

punctuation writing task: an e-mail or letter to a friend about a day (or

night) out think about the topic, spell éheck, understand an ![]() autobiography, order information, use

articles writing task: a short autobiography

autobiography, order information, use

articles writing task: a short autobiography

understand directions, use punctuation, use prepositions, spell check, write directions writing task: directions to your house or flat for a classmate

![]()

![]() understand different texts, describe a

place, use words that go together, use punctuation, spell check writing task:

an e-mail to a friend describing two hotels

understand different texts, describe a

place, use words that go together, use punctuation, spell check writing task:

an e-mail to a friend describing two hotels

![]()

understand a story, understand time markers, order a story, spell check, check for mistakes, talk about the topic writing task: a story about a special experience

think about the topic, understand a description, understand they, spell check, make sentences, talk about the topic writing task: a short article describing and comparing transport in two places

talk about the topic, describe a picture, spell check, use articles, write about a picture writing task: a description of a picture or photo

talk about the topic, understand

invitations, use prepositions, understand replies, write sentences, ![]() spell check writing task: an

invitation to a birthday celebration

spell check writing task: an

invitation to a birthday celebration

understand what the text is for, understand style, use set phrases, spell check, talk about the topic writing task: a thank you or congratulations card

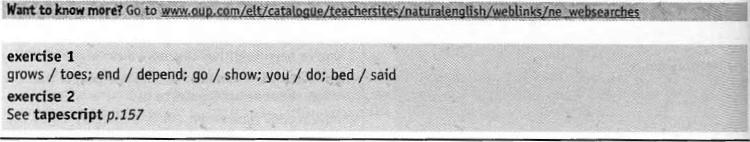

pronunciation in natural English elementary

|

book stress p.g

stress p.18 stress p.19 |

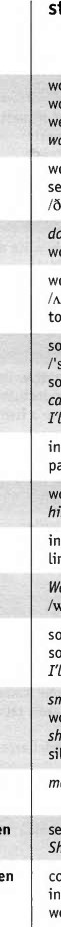

help with pronunciation and listening sections (units: 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14) pronunciation listening

word stress p.21 key words p.21 |

|

|

/ta'geða/ p.36

p.39 W, /i•J, /er/, and /æ/ p.42 and can't /ka:nt/ p.43 p.44

p.51 tense endings with /ld/ p.51

p.64 p.67

prrf3:/ p.76 law, /er/, and /o:/ p. 79 spelling problems, e.g thumb /9Am/ p.82 and shall 1 ,'jalal/ p.84 /sm3:1a/ than /ðan/ p.87 stress p.90 /SUd/ p.91

/maosli/ p.99 stress p.112 p. 113 stress and intonation p.115 |

sounds /ð/, 19/ p.37 weak forms p.37 |

|

|

sounds /o:/, /3•J, and ID/ p.53 prediction (1) p.53 |

||

|

sounds /J/, /tJ/, and Id3/ p.69 prediction (2) p.69

sounds and spelling /o:/, W, and 10/ connected speech p.85 p.85

|

||

|

consonant groups p. 101 being an active listener p.101

listening to a song p.117 linking p.117 |

||

student's

student's

![]() unit one word

word weak would

unit one word

word weak would

unit two word sentence

/ð/ p.19

![]() unit three do you word

unit three do you word

unit four word W p.35 together

unit five sound /

/'SDS1d31ZJ sounds can /kan/ I'll lad/

unit six intonation past

unit seven word

unit eight intonation linking

![]() unit nine Would

unit nine Would

/wod ja

unit ten sounds sound / I'll

unit eleven smaller word should silent t

unit twelve mostly

unit thirteen sentence Shall

unit fourteen contractions intonation word

extended speaking

During the extended speaking activity at the end of each unit, note down examples of .

• good language use

• effective communication strategies

(turn-taking, interrupting. inviting others to speak, etc.)

• learner errors

• particular communication problems

Make sure you allow time for feedback at the end of the lesson. You can use the notes you make above to praise effective language use and communication or, if necessary, to do some remedial work.

Photocopiabte @ Oxford University Press 2006

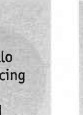

in unit one ...

listening how to ... say hello

p.16

wordbooster countries and nationalities numbers (1)

p.20

reading questions, questions

|

to . . . say hello 75—90 mins lead-in • If this is your first lesson with the class, you will probably start by introducing yourself and calling the register. The students won't remember many of the names (unless they already know each other), so the lead-in has a dual purpose: to present two natural ways of introducing oneself; and for students to find out the names of others in the group. Ask the class to look at the pictures and make sure that they understand that 2 people are meeting at the college for the first time. play the recording for exercise 1. The task is very simple but students may not know hi. With a multilingual class, you can explain that hi is common in spoken English, especially among young people. If you have a monolingual group and you speak the learners' mother tongue, see the troubleshooting box on the right. • Play the recording again (exercise 2) and elicit an accurate pronunciation model of meet you. Practise it before learners work with a partner. Students need to be aware at this very early stage that the way we say words in connected speech may be different from the way they are written down. See the language point on the right for ways of saying hello. While the students mingle in exercise 3, move round and monitor. In the early stages of an elementary course some learners may feel quite nervous, so it's important to give lots of praise and encouragement. |

|

listen to this • Put the students in pairs. See troubleshooting on the right. The students can probably deduce the answers to exercise 1 from the pictures, but don't confirm their answers yet. Play the first part of recording 1.2 (exercise 2) and elicit the answer. The purpose of this short initial listening is so that the students can tune in to the voices of the speakers with a simple task. If they can, they will feel more confident about the whole conversation, especially as it begins by replaying the first part. In other words, learners are not suddenly exposed to a long passage with unfamiliar voices and an unknown topic. • When you are ready, move on to exercise 3. The answers to exercise 1 are not in the same order on the recording, so the students may need to listen twice. • You will have to do recording 1.3 as the students need the information to talk about these people in the grammar section that follows. Before they listen, get them to read the sentences first. The names Tim and Jim may be unfamiliar, so show them how they are pronounced. Play the recording (exercise 4). Students can check in pairs while you monitor. If some answers are wrong, play the recording again. If not, go through them with the class. The last stage involves playing the recording while students look at the tape-script. We wouldn't recommend this until you have already exploited the recording for comprehension, but many students enjoy listening to and reading the tapescript, and it can help them to realize that words they recognize when written down may sound different in spoken English. |

|

help with pronunciation

an sounds the alphabet listening: asking for help |

|

![]()

p.22

test yourself!

p.25

wordlist

p.130

-introduce yourse using natural EngHsh phrases

listen to two people meeting for the first Itime

'focus on be positive -and negative learn and practise jobs oyocabulary focus on a / an

(Calk to another stude

About

yourself

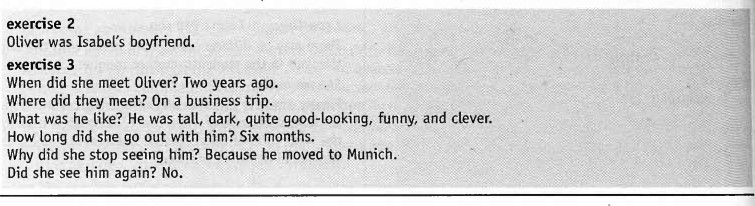

'xercise 1

|

students |

see tapescript p. 146 exercise 2 et you /'mi:t ju/

Gercise 2

Paris

•ercise 3

Harc is 21, a student, single.

is from Canada, a teacher, married. (exercise 4

3 university an English teacher 4 America

troubleshooting use of the mother tongue

During the course you wilt need to point out certain language as being either formal (generally used more in written English) or informal (generally used more in spoken English). Students need to be aware of this stylistic difference, and the words formal and informal. To explain this in English to elementary learners might be difficult, so this is an occasion when the use of the mother tongue is a sensible option. The difference between hello and hi is largely one of style — hi is more informal.

'Want to know more? GO to learners p. 160

language point saying 'hello'

Even at elementary level, some learners may already know how do you do? or how are you? If so, you may need to explain that how do you do? is now reserved for quite formal situations. How are you? is the most common way of greeting people, but only when you already know them.

troubleshooting pair work in listening activities If your class is not used to pair and group work, you may need to explain the purpose of it, in the mother tongue if necessary.

Pair and group work can be used in many different types of activity, and for different purposes. In listening activities, it can be used:

- before listening, e.g. to predict what might be said, to brainstorm vocabulary that might arise, to arouse interest in the topic through discussion or personalization, etc.

- after listening. e.g. once students have listened to a recording, they compare answers to a task with a partner. This can give them confidence before they give their answers more publicly in open class. You can monitor this stage to assess how well individuals have understood the recording, which will indicate to you whether they need to hear it again. After that, pair / group work can be used to practise the content of the listening (dialogue practice or role play), to give opinions on the topic, etc.

Want to know more? Go to pre-intermediate teachefs book, how to do pair and groúóZL$ -work p.146

|

grammar be • The students were exposed to he's (he is) in the previous exercise, but now they have to say it themselves in exercise 1. This is also their first exposure to phonemic script lhi:z/. Highlight the /i:/ sound and then model it in he's. You could then put the sentence on the board: Marc's from France, and he's ??? Elicit a correct answer from the class then write it on the board. If you are confident the class understands, put them in pairs to write three more things about Marc, beginning he's . If not, elicit one more answer from the class before the pairwork. • Repeat the procedure for she's in exercise 2, but let the students write down all four things about Jennifer in pairs. Check the answers — ask a number of students to pronounce the correct answers as you check — then go on to exercise 3. As this is the first table for students to complete, you could do it from the board as a class. Use a different coloured pen (or chalk) for the different forms of be and elicit the answers from the class as you write it up. Collaborative work like this using the board is very good for class rapport. Yant to know more? Go • As you go through the table, point out that contracted forms are very common in spoken English, but say that contractions in positive short answers are not used or ¥4&-s-ke4). For the alternative negative forms, see language point on the right. • You could do exercise 4 round the class and then in pairs. It is important at this early stage that students are reinforcing correct answers when they work in pairs, and it will help their confidence to grow. For exercise 5, again model it first before the pairwork. • Exercise 6 is a continuation of the previous exercise, but this time students have to write the questions, which provides a change of pace. We have suggested two sentences for exercise 7, but you could increase it to four or five. Finally there is the language reference section. This contains not only a fuller explanation of the grammar the students have just studied, but also additional exercises. -want to know Gou language'eferencea'eggi |

|

vocabulary jobs • There are certain gender issues with this vocabulary. See language point on the right. Students can do exercise 1 individually, then you can check the answers with the class. Point out that we need the indefinite article with the names of jobs, and if any of your learners are likely to make this mistake, write correct and incorrect examples on the board:

The choice between a and an is in the next section, so don't worry about it at this stage. • At the same time you can start to focus on the pronunciation. We have marked the stress on the first example. You can illustrate this by saying a word with the correct stress then saying it with the wrong stress. Make it absolutely clear which is right, then test your students to check they can hear the difference. • Play the recording (exercise 2). At the end check the answers and drill the correct pronunciation. When they work in pairs in exercise 3, they have to put the words back into short sentences. • Although the students haven't come to present simple questions yet, many will be familiar with the form, and you can teach the question What do you do? as a fixed phrase or vocabulary item. You can paraphrase the question as What's yourjob? If your students are still at school I college you could choose one student and ask him / her about the future. (Perhaps write a future year on the board.) Put a question mark by it and say doctor? teacher? what? Teach the question and answer What do you want to be? I want to be a (doctor). Some students will already know the name of their job in English; others will have to look them up in a bilingual dictionary or ask you for a translation. • When they do exercise 4, it is possible that other students won't understand the name of the job they hear. What should the speaker do here? See troubleshooting on the right for a suggestion. At the end, you could add some of the new jobs to the board if you think they are useful. |

Gercise 1

•Marc's from Paris, he's 21, he's a business student, and us single.

exercise 2 from Toronto, she's a business teacher, and §h€s married.

exercise 3

I'm a teacher I'm not a teacher

Hú a doctor

She's a student She isn't a student

exercise 4

Jennifer isn't ![]() Ottawa, she's from Toronto. She's a

business teacher. She's from Canada. She isn't single, she's married.

Ottawa, she's from Toronto. She's a

business teacher. She's from Canada. She isn't single, she's married.

Marc isn't from England, he's from France. He's a business student. Marc isn't married, he's single. He isn't 24, he's 21.

Tim's from America. Tim isn't a business teacher, he's an English teacher. He isn't from Toronto, he's from San Francisco.

|

exercise 5 |

|

|

|

.1 Yes, heis |

3 No, he isn't |

5 Yes, she is |

|

No, she isn't Gercise 1 |

4 No, she isn't |

6 NO, he isn't |

|

'1 a housewife |

6 a journalist |

|

|

a shop assistant 7 an office worker |

||

|

a waiter 8 a police officer |

||

|

a lawyer 9 an engmeer |

||

|

a businessman / woman 10 an actor |

||

'exercise 2 engineer, office yorker, niter, layyer, Nice officer, businessman / woman, shop assistant, actor, ioucnalist

language point form problems with be

You need to highlight these forms very clearly as there are common problems from Ll transfer, e.g. omitting the pronoun (is-a—teachev) or omitting the verb (she teaehe¥). The other common error is mixing up the pronouns he and she. This error can persist for a tong time with some students, so you may need to correct it quite firmly.

The language reference on p.130 points out the two different ways of forming a negative in the third person (he / she isn't or he's / she's not). We have only included one form here, but you could highlight the alternative form. Both are common in spoken English.

language point gender in 'jobs'

Some jobs have the same word regardless of whether the job is performed by a man or woman, e.g. lawyer and journalist. Other jobs make a distinction between the sexes, e.g. waiter / waitress, businessman / businesswoman, or the more recent distinction between housewife and house husband. A third group have forms which may or may not denote the sex, e.g. an actor can be male or female but an actress can only be female; a firefighter can be male or female but fireman is only male. For the police there are three possibilities: policeman, policewoman, or police Officer.

We have given just one form in most cases — the most common form — but you may wish to discuss this with your class, particularly if you teach in a country where the 'less' common form is actually more frequent, e.g. if 'waitresses' are much more common than 'waiters'.

troubleshooting unknown lexis

If student B doesn't understand student A's job, tell student A to try to explain it using gesture or paraphrase. They may struggle to do this with some jobs, but most low-level students have to deal with this problem at some stage, so it's not a bad idea to present them with this kind of challenge. With a monolingual group, we would also suggest you allow the use of translation as a last resort if paraphrase and gesture don't work.

grammar a / an

• Draw your students' attention to the schwa la/ with a and an. Model the sound to show them how these words are usually pronounced.

Ask learners to do exercise 1. They may realize that the answer is already in the list of jobs vocabulary; if so, good for them. Check their understanding by asking for further examples (office worker and journalist are two from the list above, but they may come up with others, e.g. an artist, a doctor). This is a simplification of the rule governing the use of a / an. For more detail, see language point on the right. Do exercise 2 for students to test their understanding of the rule, and the exercises in the language reference if you want further practice.

speaking i€s your turn!

• While students complete exercise 1, monitor their writing to check their answers and spelling. Those still at school or university can put student in the 'job' category. You could also add a category about 'age'. Il's a sensitive issue, but if you are sure it won't cause offence, you could include it. The pair practice is there to build their confidence.

• Exercise 2 provides more practice but in a group Of three the dynamic changes, with potentially more shifts in turn-taking between the individuals. Finally, in exercise 3, students have to move from first to third person for another shift in the type of practice. Note that students need to say that's and not this is as they are pointing somebody out and not introducing them. Do the can you remember activity. See troubleshooting on the right.

Learners could complete the middle column in exercise 1 in pairs, but tell them not to fill in the nationalities at this stage. Understanding is not usually a problem with the names of countries, but pronunciation is, so they can check by listening to recording 1.5 (exercise 2), which gives them a pronunciation model. Afterwards, give them a minute to repeat the words quietly to themselves (this is sometimes called a 'mumble drill'). You can move round and listen while they do this.

• They can do exercise 3 together. Check their answers, then play the recording (exercise 4). This time the students underline the main stress. Check the answers.

Vant to

• Finally they can do exercise 5. We have included two more useful chunks of language which they can learn as fixed phrases (1 don't know and I'm not sure); they may need them during the activity.

• For more work on the use of the definite article or zero article with the names of countries, see workbook, expand your grammar, p.6.

At this level learners can never have too much practice with numbers. They need to know them and use them, but also process them when they are spoken quickly. In exercise 1 students have to do this with phone numbers, then practise them in exercise 2. For the pronunciation of O (zero), see language point on the right. The exercise also provides practice in contrastive stress as student B corrects a wrong number given by student A.

• The natural box teaches another fixed phrase (What's your phone / mobile number?) along with the confirmation of the number (Yeah / Yes that's it.). This is very straightforward but learners are not always good at providing this type of response. After they complete the task (exercise 3), get them to stand up for exercise 4 and move round the class. If they can't remember their number (phone or mobile), tell them to invent one. Monitor and help I correct where necessary.

• You could turn exercise 5 into a race — the first pair to finish puts up their hands. The answers (exercise 6) are on a recording to provide further pronunciation models. For further practice see ideas plus on the right.

Uercise 1

Put an before words that begin a, e, i, o, u, e.g. actor, engineer

Put a before all other letters, e.g. zaiter, teacher

2

|

l a 3 an 4 an 6 an n you remember |

7 an |

|

|

meet 3 an |

5 |

thirty |

|

from 4 do 'exercises 1, 2, 3, and 4 |

6 |

isn't ('s not) |

|

COUNTRY |

NATIONALITY |

|

|

'France |

French |

|

|

Germany |

German |

|

|

Japan |

Japanese |

|

|

Spain |

Spanish |

|

|

Argentina SA |

Argentinian |

|

|

China |

Chinese |

|

|

Italy |

Italian |

|

|

•Brail SA |

Brazilian |

|

|

Thailand |

Thai |

|

|

Eland |

Polish |

|

|

86tain exercise 5 |

British |

|

|

She's Brazilian. |

4 It's Chinese. |

|

|

'2 It's British. |

5 She's Japanese. |

|

|

He's Italian. |

6 Theyre Argentinian. |

|

•exercise 1 tape-script p. 146 exercise 3 Re tapescript p. 146 •exercise 6 see tapescript p.145

language point o / an

The choice between a and an depends on pronunciation rather than spelling. Thus:

— we can use an before a consonant if it is silent or pronounced as a vowel: an hour (silent 'h') an MP (the M is pronounced /em/)

— we can use a before 'u' when it is pronounced /ju:/, or 'o' when it is pronounced

a uniform a university student a one-week stay

troubleshooting recycling

We have included a short can you remember activity at various points in each unit because elementary learners are inevitably exposed to a lot of new input each lesson, and it is easy to forget things in an unfamiliar language. This is another form of recycling in addition to the extended speaking activities, and review and test yourself! sections. These activities occur either at the beginning or end of a lesson. They could therefore serve as a warmer or a way of winding down, but provide you and the Learners with a quick check on what they can remember from either the last lesson or the one just finished.

language point the number 'O'

The number O is usually pronounced /ao/ in phone numbers in British English but zero in American English. British speakers normally use zero when they are talking about temperature, e.g. ten degrees below zero. In mathematics, the number O is usually written as nought /no:t/, 0.7 (nought point seven). However, if someone used zero in all of these contexts, they would be clearly understood.

ideas plus maths

Put about fifteen numbers on the board, then teach + (and) and - (minus). Students can then give each other little maths tests using the numbers, e.g. What's fifteen and seven? Twenty-two.

|

questions, questions 75-90 mins grammar questions with be Can you remember ? provides some quick revision, and also ensures that students don't have their heads in their books to start the lesson. Make sure they shut their books or cover the wordbooster page opposite. Elicit an example first. then give pairs one minute. Check the answers at the end. Direct students to the first column of the table in exercise 1, and elicit the answer to the first question, i.e. Are you a new student? Students can compare answers or work together on this exercise. Play the recording to check the answers to exercise 2. Stop the tape after each one, elicit the missing words and write them on the board, or invite a stronger student who may appreciate the challenge, to ensure that the answers are absolutely clear to everyone. Encourage students to write the contractions for is; you could also remind them that contractions are normal in spoken English. However, we don't usually write the contraction for are. Give students a minute to think about their answers in exercise 3. If necessary, pre-teach I don't know and I'm not sure: see troubleshooting on the right. Before students work in pairs in exercise 4, see troubleshooting on the right. After exercise 4, do the language reference and practice exercises or set them for homework. |

|

read on • This first reading activity in the book is deliberately simple; students should be able to relate easily both to the content and the text type. For many learners (particularly those with Roman script). reading is more accessible than listening as they can process the text in their own time. Nevertheless, you don't want students to be reading in great detail, so the simple questions in exercise 1 do not rely on a detailed understanding of the text. Give them about two minutes, and make clear that they only need to answer those two questions at this stage. • Exercise 2 focuses on word order in questions. Check answers as a class before students ask and answer in pairs. Check the answers to exercise 3 at the end. • The context continues in exercise 4, in which students listen intensively to the short dialogue. The language is likely to be familiar, although students do not always know Fine, thanks at this level. Focus on the pronunciation in exercise 5 and drill the weak forms la/, land/, or use the tape as a model if you don't feel confident about your own pronunciation. Students can mingle for exercise 6 and practise the dialogue with lots of students, using their own names. See ideas plus on the right. |

|