ПОДОЙДЕТ ДЛЯ 9, 10, 11 КЛАССОВ

ТЕМА СТИХИЙНЫЕ БЕДСТВИЯ

ЭТО ТАИНСТВЕННОЕ ЯВЛЕНИЕ НЕ ОСТАВИТ РАВНОДУШНЫМ НИКОГО.

Торнадо – одно из самых опасных и разрушительных явлений природы, ежегодно уносящее сотни жизней по всей планете. Причины появления этих гигантских вихрей известны людям с давних времен, однако до сих пор никто так и не научился их усмирять.

PRESENTATION

IN

ENGLISH

TORNADO

A tornado is a violently rotating column of air that is in contact with both the

surface of the earth and a cumulonimbus cloud or, in rare cases, the base of

a cumulus cloud. They are often referred to as twisters or cyclones, although the

word cyclone is used in meteorology, in a wider sense, to name any closed low

pressure circulation. Tornadoes come in many shapes and sizes, but they are

typically in the form of a visible condensation funnel, whose narrow end touches

the earth and is often encircled by a cloud of debris and dust. Most tornadoes

have wind speeds less than 110 miles per hour (177 km/h), are about 250 feet

(76 m) across, and travel a few miles (several kilometers) before dissipating.

The most extreme tornadoes can attain wind speeds of more than 300 miles per

hour (483 km/h), stretch more than two miles (3.2 km) across, and stay on the

ground for dozens of miles (more than 100 km).

• Various types of tornadoes include the landspout, multiple

vortex tornado, and waterspout. Waterspouts are characterized

by a spiraling funnelshaped wind current, connecting to a

large cumulus or cumulonimbus cloud. They are generally

classified as nonsupercellular tornadoes that develop over

bodies of water, but there is disagreement over whether to

classify them as true tornadoes. These spiraling columns of air

frequently develop in tropical areas close to the equator, and

are less common at high latitudes. Other tornadolike

phenomena that exist in nature include the gustnado, dust

devil, fire whirls, and steam devil; downbursts are frequently

confused with tornadoes, though their action is dissimilar.

Tornadoes have been observed on every continent except Antarctica.

However, the vast majority of tornadoes occur in theTornado Alley region of

the United States, although they can occur nearly anywhere in North America.

They also occasionally occur in southcentral and eastern Asia, northern and

eastcentral South America, Southern Africa northwestern and southeast

Europe, western and southeastern Australia, and New Zealand. Tornadoes can

be detected before or as they occur through the use of PulseDoppler radar by

recognizing patterns

in velocity and reflectivity data, such as hook

echoes ordebris balls, as well as through the efforts of storm spotters.

There are several scales for rating the strength of tornadoes.

The Fujita scale rates tornadoes by damage caused and has been

replaced in some countries by the updated Enhanced Fujita Scale.

An F0 or EF0 tornado, the weakest category, damages trees, but not

substantial structures. An F5 or EF5 tornado, the strongest category,

rips buildings off their foundations and can deform largeskyscrapers.

The similar TORRO scale ranges from a T0 for extremely weak

tornadoes

known

tornadoes. Doppler radar data, photogrammetry, and ground swirl

patterns (cycloidal marks) may also be analyzed to determine

intensity and assign a rating.

the most

powerful

to

T11

for

Etymology

The word tornado is an altered form of the Spanish word tronada,

which means "thunderstorm". This in turn was taken from the Latin tonare,

meaning "to thunder". It most likely reached its present form through a

combination of the Spanish tronada and tornar ("to turn"); however, this

may be a folk etymology. A tornado is also commonly referred to as a

"twister", and is also sometimes referred to by the oldfashioned colloquial

term cyclone.The term "cyclone" is used as a synonym for "tornado" in the

oftenaired 1939 film The Wizard of Oz. The term "twister" is also used in

that film, along with being the title of the 1996 tornadorelated film Twister.

• A tornado is "a violently rotating column of air, in contact with the

ground, either pendant from a cumuliform cloud or underneath a

cumuliform cloud, and often (but not always) visible as a funnel

cloud“. For a vortex to be classified as a tornado, it must be in

contact with both the ground and the cloud base. Scientists have

not yet created a complete definition of the word; for example,

there is disagreement as to whether separate touchdowns of the

same funnel constitute separate tornadoes. Tornado refers to

the vortex of wind, not the condensation cloud.

Funnel cloud

A tornado is not necessarily visible; however, the intense low pressure caused by the high wind

speeds (as described by Bernoulli's principle) and rapid rotation (due to cyclostrophic balance)

usually causes water vapor in the air to condense into cloud droplets due to adiabatic cooling. This

results in the formation of a visible funnel cloud or condensation funnel.

There is some disagreement over the definition of funnel cloud and condensation funnel.

According to the Glossary of Meteorology, a funnel cloud is any rotating cloud pendant from a

cumulus or cumulonimbus, and thus most tornadoes are included under this definition. Among many

meteorologists, the funnel cloud term is strictly defined as a rotating cloud which is not associated

with strong winds at the surface, and condensation funnel is a broad term for any rotating cloud

below a cumuliform cloud.

Tornadoes often begin as funnel clouds with no associated strong winds at the surface, and not all

funnel clouds evolve into tornadoes. Most tornadoes produce strong winds at the surface while the

visible funnel is still above the ground, so it is difficult to discern the difference between a funnel

cloud and a tornado from a distance.

Size and shape

Most tornadoes take on the appearance of a narrow funnel, a few hundred yards (meters) across, with a small cloud

of debris near the ground. Tornadoes may be obscured completely by rain or dust. These tornadoes are especially

dangerous, as even experienced meteorologists might not see them. Tornadoes can appear in many shapes and sizes.

Small, relatively weak landspouts may be visible only as a small swirl of dust on the ground. Although the

condensation funnel may not extend all the way to the ground, if associated surface winds are greater than 40 mph

(64 km/h), the circulation is considered a tornado. A tornado with a nearly cylindrical profile and relative low height is

sometimes referred to as a "stovepipe" tornado. Large singlevortex tornadoes can look like large wedges stuck into the

ground, and so are known as "wedge tornadoes" or "wedges". The "stovepipe" classification is also used for this type

of tornado, if it otherwise fits that profile. A wedge can be so wide that it appears to be a block of dark clouds, wider

than the distance from the cloud base to the ground. Even experienced storm observers may not be able to tell the

difference between a lowhanging cloud and a wedge tornado from a distance. Many, but not all major tornadoes are

wedges. Tornadoes in the dissipating stage can resemble narrow tubes or ropes, and often curl or twist into complex

shapes. These tornadoes are said to be "roping out", or becoming a "rope tornado". When they rope out, the length of

their funnel increases, which forces the winds within the funnel to weaken due to conservation of angular

momentum. Multiplevortex tornadoes can appear as a family of swirls circling a common center, or they may be

completely obscured by condensation, dust, and debris, appearing to be a single funnel.

In the United States, tornadoes are around 500 feet (150 m) across on average and

travel on the ground for 5 miles (8.0 km).However, there is a wide range of tornado

sizes. Weak tornadoes, or strong yet dissipating tornadoes, can be exceedingly narrow,

sometimes only a few feet or couple meters across. One tornado was reported to have a

damage path only 7 feet (2 m) long. On the other end of the spectrum, wedge tornadoes

can have a damage path a mile (1.6 km) wide or more. A tornado that affected Hallam,

Nebraska on May 22, 2004, was up to 2.5 miles (4.0 km) wide at the ground.

In

terms of path

length,

the TriState Tornado, which affected parts

of Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana on March 18, 1925, was on the ground continuously for

219 miles (352 km). Many tornadoes which appear to have path lengths of 100 miles

(160 km) or longer are composed of a family of tornadoes which have formed in quick

succession; however, there is no substantial evidence that this occurred in the case of the

TriState Tornado. In fact, modern reanalysis of the path suggests that the tornado may

have begun 15 miles (24 km) further west than previously thought.

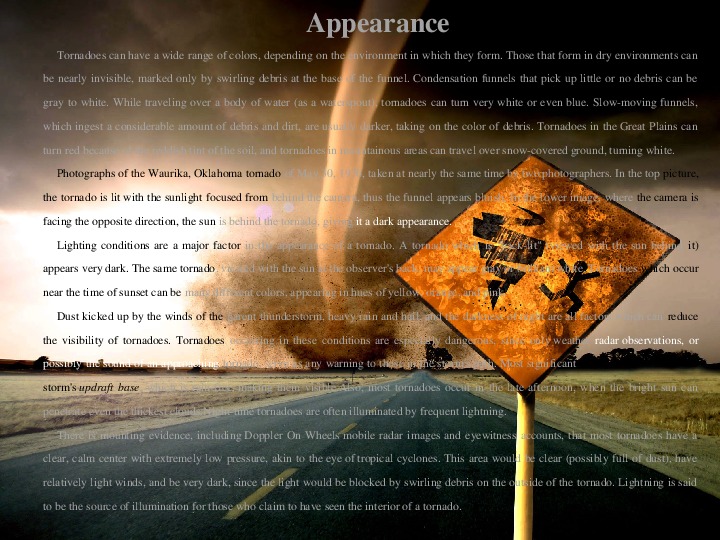

Appearance

Tornadoes can have a wide range of colors, depending on the environment in which they form. Those that form in dry environments can

be nearly invisible, marked only by swirling debris at the base of the funnel. Condensation funnels that pick up little or no debris can be

gray to white. While traveling over a body of water (as a waterspout), tornadoes can turn very white or even blue. Slowmoving funnels,

which ingest a considerable amount of debris and dirt, are usually darker, taking on the color of debris. Tornadoes in the Great Plains can

turn red because of the reddish tint of the soil, and tornadoes in mountainous areas can travel over snowcovered ground, turning white.

Photographs of the Waurika, Oklahoma tornado of May 30, 1976, taken at nearly the same time by two photographers. In the top picture,

the tornado is lit with the sunlight focused from behind the camera, thus the funnel appears bluish. In the lower image, where the camera is

facing the opposite direction, the sun is behind the tornado, giving it a dark appearance.

Lighting conditions are a major factor in the appearance of a tornado. A tornado which is "backlit" (viewed with the sun behind it)

appears very dark. The same tornado, viewed with the sun at the observer's back, may appear gray or brilliant white. Tornadoes which occur

near the time of sunset can be many different colors, appearing in hues of yellow, orange, and pink.

Dust kicked up by the winds of the parent thunderstorm, heavy rain and hail, and the darkness of night are all factors which can reduce

the visibility of tornadoes. Tornadoes occurring in these conditions are especially dangerous, since only weather radar observations, or

possibly the sound of an approaching tornado, serve as any warning to those in the storm's path. Most significant tornadoes form under the

storm's updraft base, which is rainfree, making them visible.Also, most tornadoes occur in the late afternoon, when the bright sun can

penetrate even the thickest clouds.Nighttime tornadoes are often illuminated by frequent lightning.

There is mounting evidence, including Doppler On Wheels mobile radar images and eyewitness accounts, that most tornadoes have a

clear, calm center with extremely low pressure, akin to the eye of tropical cyclones. This area would be clear (possibly full of dust), have

relatively light winds, and be very dark, since the light would be blocked by swirling debris on the outside of the tornado. Lightning is said

to be the source of illumination for those who claim to have seen the interior of a tornado.

Rotation

Tornadoes normally rotate cyclonically (when viewed from above, this is counterclockwise in the northern

hemisphere and clockwise in the southern). While largescale storms always rotate cyclonically due to

the Coriolis effect, thunderstorms and tornadoes are so small that the direct influence of the Coriolis effect is

unimportant, as indicated by their large Rossby numbers. Supercells and tornadoes rotate cyclonically in

numerical simulations even when the Coriolis effect is neglected. Lowlevel mesocyclones and tornadoes owe

their rotation to complex processes within the supercell and ambient environment.

Approximately 1 percent of tornadoes rotate in an anticyclonic direction in the northern hemisphere.

Typically, systems as weak as landspouts and gustnadoes can rotate anticyclonically, and usually only those

which form on the anticyclonic shear side of the descending rear flank downdraft in a cyclonic supercell. On

rare occasions, anticyclonic tornadoes form in association with the mesoanticyclone of an anticyclonic

supercell, in the same manner as the typical cyclonic tornado, or as a companion tornado either as a satellite

tornado or associated with anticyclonic eddies within a supercell.

Electromagnetic, lightning, and other effects

Tornadoes emit on

the electromagnetic spectrum, with sferics and Efield effects detected. There are observed

correlations between tornadoes and patterns of lightning. Tornadic storms do not contain more lightning than other storms

and some tornadic cells never produce lightning. More often than not, overall cloudtoground (CG) lightning activity

decreases as a tornado reaches the surface and returns to the baseline level when the tornado lifts. In many cases, intense

tornadoes and

thunderstorms exhibit an

increased and anomalous dominance of positive polarity CG

discharges. Electromagnetics and lightning have little or nothing to do directly with what drives tornadoes (tornadoes are

basically a thermodynamic phenomenon), although there are likely connections with the storm and environment affecting

both phenomena.

Luminosity has been reported in the past and is probably due to misidentification of external light sources such as

lightning, city lights, and power flashes from broken lines, as internal sources are now uncommonly reported and are not

known to ever have been recorded. In addition to winds, tornadoes also exhibit changes in atmospheric variables such

astemperature, moisture, and pressure. For example, on June 24, 2003 near Manchester, South Dakota, a probe measured a

100 mbar (hPa) (2.95 inHg) pressure decrease. The pressure dropped gradually as the vortex approached then dropped

extremely rapidly to 850 mbar (hPa) (25.10 inHg) in the core of the violent tornado before rising rapidly as the vortex

moved away, resulting in a Vshape pressure trace. Temperature tends to decrease and moisture content to increase in the

immediate vicinity of a tornado.

of milDetection

Rigorous attempts to warn of tornadoes began in the United States in

the mid20th century. Before the 1950s, the only method of detecting a

tornado was by someone seeing it on the ground. Often, news of a tornado

would reach a local weather office after the storm. However, with the

advent of weather radar, areas near a local office could get advance

warning of severe weather. The first public tornado warnings were issued

in 1950 and the first tornado watches and convective outlooks in 1952. In

1953 it was confirmed that hook echoes are associated with tornadoes. By

recognizing

thunderstorms probably producing tornadoes from dozens es away.

signatures, meteorologists could detect

these

radar